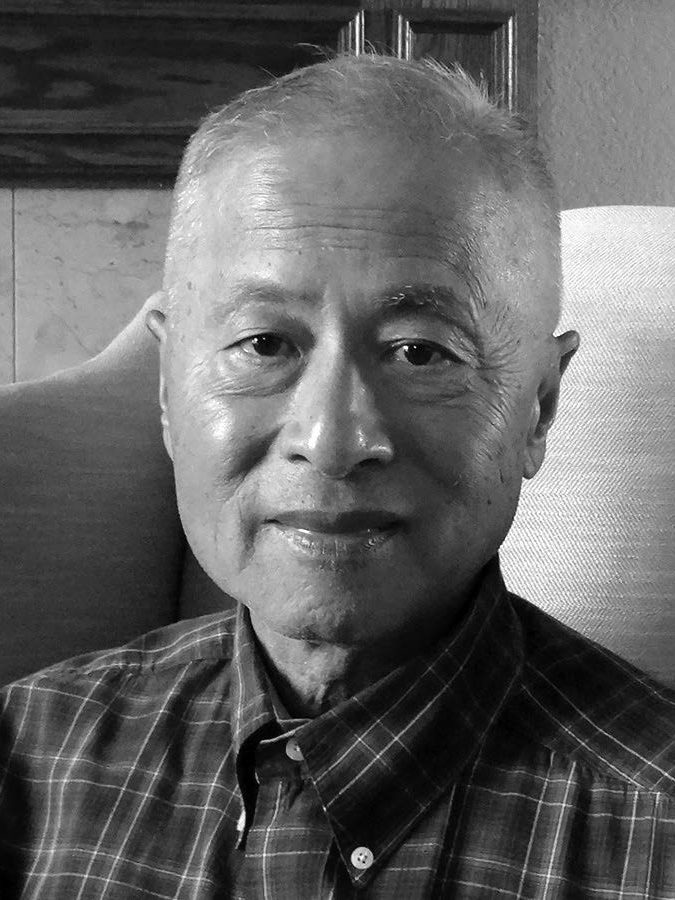

Excerpt of a memoir by Chinese-American writer Roy Cheng Tsung, from his new book Ox Horn Bend, just released from Passager Books.

6 minutes

TRANSCRIPT

After Roy Cheng Tsung escaped communist China in 1974, he spent the next several decades trying to learn why his father moved the family from New York, where Roy was born, back to China in the early days of the Maoist regime. He tells that story in his new memoir Ox Horn Bend, which Passager just published. In this scene, he’s escaped from China to Hong Kong and is trying to get back to the United States.

Would the Americans believe my story and let me return? After all, I was no longer a twelve-year-old boy fresh out of New York City, but a thirty-three-year-old adult who had just crossed the Communist border . . .

In July, 1974, less than two months after we arrived in Hong Kong, I wrote to American Consul General Charles T. Cross. “It has been my fervent desire to return to the land where I was born,” I wrote, enclosing a photostatic copy of my birth certificate, and asking for help. “Of course,” I continued, “I realize you will no doubt consider that I have just come from a country that has been hostile to the United States for over two decades. But I earnestly hope you will also take into consideration that I left China because I could no longer live and work in a land with no freedom of thought and expression, no freedom from fear and suspicion. I resolved to leave China in spite of all the difficulties and obstacles.”

It was two years after President Richard Nixon’s famous handshake with China’s leaders, but a great deal of mistrust still stood in the way. And here I was, a lone individual just “in from the Cold” showing up and claiming to be an American-born citizen. It was almost like a page out of a novel.

Consul Jerome Ogden examined my fragile birth certificate and gave it to his assistant. The light blue document was fading and full of creases, but the information was all there, and even the signature of Mayor La Guardia was still visible . . .

The Consul studied the document. “Your father was a Chinese diplomat,” he noted. “Do you realize that you may not be a U.S. citizen because of your father’s status when you were born?”

“I was born outside of the Chinese diplomatic grounds,” I replied to Consul Odgen.

The American Consul nodded. I detected a faint smile on his face. He probably realized that I had come prepared. But the assistant asked bluntly, “Why didn’t you claim your American citizenship until now?”

I could almost hear my father’s voice. “Remember to use the word ‘jeopardize,’” he said.

“Foreign legations are guarded by Chinese soldiers and secret police,” I replied. “I could not approach them without jeopardizing myself and my parents.”

A moment of silence. Outside the window, I could see the Stars and Stripes waving.

“Didn’t you have an American passport before?” asked the assistant. I shook my head. “Since you are American born, why didn’t your parents get you an American passport while you were in the U.S.?”

I wondered where his question was leading. “I really don’t know,” I admitted. “I was just a child and always traveled as a minor with my mother.”

Consul Odgen smiled and said, “It would have been helpful if you had a U.S. passport before. Your documents are helpful, but we need to have something that can prove that you are the person in the birth certificate. You went to school in New York. Do you have a graduation photograph, perhaps?”

Unfortunately, the only picture I had of my graduation from Public School 165 was confiscated in Beijing by the Red Guards when my father was persecuted. My heart sank.

“How did you manage to keep your birth certificate?” asked the assistant.

“My mother hid it in her slipper during the Cultural Revolution.”

I saw a brief look of surprise and admiration on their faces.

“Write to your school,” Consul Ogden suggested. “They may have something.” I sensed that he was trying to help me and I appreciated it.

. . .

Excerpts from Roy Cheng Tsung’s memoir Ox Horn Bend.

To buy Ox Horn Bend or Roy’s first book Beyond Lowu Bridge, or to learn more about Passager and its commitment to writers over 50, go to passagerbooks.com. You can download Burning Bright from Spotify, Apple and Google Podcasts, and various other podcast apps.

Before we end this episode of Burning Bright, here’s Passager’s art director and graphic designer Pantea Tofangchi:

“Passager is a small literary press dedicated to older voices, a generation vital to our survival. We are working hard to ensure that Passager’s mission continues for decades to come. My responsibility is to make the most beautiful home for our writers’ words, from the cover to all the white space that hugs the letters. I Hope every time that you read one of our issues or books, you are reminded how you have been part of it. Please join me and our Passager family today in celebrating this beautiful tradition of kindness and generosity. Even a small donation can go a long way to sustaining us. Go to Passagerbooks.com and click on “donate” at the top of the page.”

It’s the season of giving. We hope you’ll give to Passager.