The Pandemic Diaries began in March, 2020, when the United States “shut down” and all but essential workers were confined to “shelter in place.” We collectively closed our doors, watched and read the news, and worried about our loved ones, ourselves, and, frankly, everyone everywhere. At Passager, we were surprised that people around the world — from Australia, India, Germany, France, Canada, Iran, Belgium, Ireland, Switzerland, and across the United States started writing to us, telling us their stories and wanting to feel connected. The Passager community became global, and each piece of correspondence added a new and important moment to the record. We decided that one thing we could do was to publish as many of these pieces as possible.

We are no longer accepting new entries to this series.

Noreen Oesterlein, Woodbury, Minnesota

Journal entry, July 4, 2022

My husband and I made it through the worst of the pandemic without getting sick. Yesterday he tested positive for Covid, but thankfully is not very ill. And I began the day today, Independence Day, feeling sorry for myself as we had plans to celebrate with family and friends. I did today what I did on a sullen, cold, end-of-winter day in March of 2020 and walked the Mississippi River trails in Saint Paul to recenter myself. In 2020 my whole being was on tumble dry high with fear of all the unknowns then; sad for all of the very sick and the dying, the families who lost beloved members, those who abruptly lost jobs, teachers and students who were in turmoil and all of the hurt in our global community. As I walked the paths back then I came upon a homeless encampment and wondered how the residents stayed warm in the freezing temperatures, how did they get food and how could they stay safe in that environment. And felt shame for my lack of gratitude for our snug and secure life. We have a warm home, we are retired so no jobs to lose and have resources for food and medical care. I made a promise to myself that day to never forget to be grateful for our good fortune. I almost broke that oath until I walked the river paths this morning and remembered.

Joanie HF Zosike, New Jersey

Journal entry, July 1, 2022

My mother Gloria passed away on January 6 at the age of 95, after a long journey with Alzheimer’s and congestive heart failure. It was devastating to lose her.

She never got COVID. That would have been too much.

Our brother Carl flew to NJ from his home in Switzerland. He is a singer with the Zurich Opera company. Apparently, little care was given for safety. In his dressing room, nine out of eleven people had come down with the virus. Despite a negative test, Carl didn’t feel well when he got on the plane. By the time he landed, he felt vile. When he arrived at our house, he retested and got a strong positive result.

All three of us had to go into quarantine and plans for the live commemoration had to be canceled. However, we held a well-attended celebration of her life on ZOOM and are now moving toward the actual burial in Los Angeles to be held in August.

People keep saying, “You guys just can’t catch a break.” But I think about all the people who, at the beginning of the pandemic, were unable to see their loved ones when they were dying and were never able to bury them. Even though we were in quarantine on the morning Mom died, the hospital allowed us to be with her during her last hours. That was a blessing for which we are deeply grateful.

Shirley Nelson, Florence, Oregon

Journal Entry, July 1, 2022

It’s back. At the Senior Retirement residence where my husband and I live, we are tested often. Earlier this week we were told a staff member had the disease and was recuperating at home. Testing resulted in 3 cases among residents. They are confined to their rooms for now; all have been completely vaccinated so should not have severe symptoms.

The rest of us are able to come and go, eat in the dining room, etc. Group social gatherings in the building are mostly canceled and we are asked to wear masks when not in our apartments. The best laid plans . . .

Nancy Buck, Chester Springs, Pennsylvania

Journal entry, November 23, 2021

I’m a 7th grade English teacher who taught in-person during the pandemic, while navigating numerous quarantines, family illnesses, a broken foot, and the death of an aging parent. This entry is from the family’s first pandemic vacation, a year to the day after the death of my father.

Waiter, there’s a mermaid in my drink. Oh, wait, I think it’s me. And look, I’m starting to swim.

I am out. Out of school. Out of my burst bubble. Out of my pandemic mindset, I think. I am dining out, literally, on Duval Street. The Key West breeze gently carries the scents of salt air and grilled fish to our streetside table at Lucy’s Retired Surfers Bar. It lifts my hair as I lean in for a family selfie. Together at last – our first family vacation since the pandemic, since the “kids’” bouts of Covid, since the loss of my father a year ago today, and the countless quarantines. My first masked airplane ride brought us to this – my most memorable dinner.

It’s not the balsamic reduction tuna lingering in my memory, nor the cocorita, garnished with perfectly toasted coconut. It’s the little plastic mermaid poised on the rim, reminding me of what I need.

My family bobs to a girl strumming and singing “Goodbye Earl.” A crowd gathers. I am surrounded by strangers, riding the same wave. I am not afraid. I sing along, far away from standing double-masked in front of my class, straining my voice to teach, knowing I am lucky, moving simultaneously from online to in-person students, wondering how many more waves we will see this school year.

With a flick of my finger, the mermaid dives in. And for the moment, she’s free. Just like me.

Mary Ellen Talley, Seattle, Washington

Journal entry, June 24, 2022

All but the youngest of our grandchildren have been vaccinated, all resumed school, and largely dropped mask wearing in classrooms, but receive notices when a student in a class has Covid. Sometimes my second-grade granddaughter will announce that she can’t play with a friend at school because someone is positive and they keep the classrooms separated during recesses. Our daughter is good about warning us when someone in her family has a known exposure in case we want to avoid a visit. Sadly, we all tend to be less “huggy.” We realize every contact includes an element of risk.

It has been our annual summer delight to take our grandchildren to see outdoor musicals at the Kitsap Forest Theater in Bremerton, Washington. This year, we took the five, eight, and thirteen-year-old to see Beauty and the Beast. We all had masks in our pockets, but didn’t wear them. We are emerging gradually and gratefully.

Kirsten Morgan, Golden, Colorado

Journal entry, May 3, 2022

For a long time, I didn’t admit it but wondered why the life I used to navigate with ease had become not only distant but also more confusing. Was it age, my first assumption? Was it the world’s increasingly erratic behavior? For the last several months, I’ve been unable to organize my existence around activities and expectations that keep me grounded. I forget obligations, I can’t recall what my calendar says, I agree to do things and then wander away from remembering. These are surely descriptors of the aging mind, but this feels different somehow — and many people of all ages are noticing the same behaviors. It’s apparently a subliminal coping mechanism that the brain, that devious organ, has developed around our protection. When we feel overwhelmed, we just shut down, and the result is that not only the big things lose their impact but the smaller things also fall victim to erratic consciousness. It’s always been known that people under stress forget things so they can focus on the task at hand — caring for a sick relative, giving attention to a newborn, fending off an abusive spouse. Survival requires prioritization, and if we won’t do it consciously, our lizard brain shoves us aside and takes over. COVID, added to already existing anxieties, opened this bag of Aeolian winds and now they can’t be stuffed back inside. We’re ever drifting farther from home and there’s always a storm coming in.

Antoinette Kennedy, Hillsboro, Oregon

Journal entry, June 8, 2022

Teach us to care and not to care. Teach us to sit still, was my poem line (Eliot’s) for the day. The bunny, cowering in the bushes, was small enough to hold in my hand. “Poor thing. That cat toyed with it,” the young woman said, and gently stroked the rabbit. Teach me to care and curse the black cat that prowls free around our apartment complex, the cat no one claims. Teach me not to care and I walked away from my anger and brought carrot and apple bits, an old towel. The woman, Lindsay, carried the wounded creature away. Teach me to care and sorrow for the besieged in Sievierodonetsk, Buffalo, and Uvalde folded into the torn body of a tiny rabbit. An hour later Lindsay texted me to say that the bunny died. Teach us not to care, so the two of us set aside our mourning and wrapped the tiny, stiff form in flowers and a cloth. Teach us to sit still. Sun warmed our bench and in passing, wind let the leaves shimmer green.

David Massey, Decatur, Georgia

Journal entry, June 19, 2022

This pandemic has increased my isolation. I am almost completely deaf, although there are some people whose voices I hear well, and this divorces me from family and friends when there is a gathering, either at our house or elsewhere. As people converse fervently on all sides of me, I hear only a great tumult, an echo chamber of disorder and cognitive impairment. I cannot participate, can only pick up one word in twenty, so I sit silently, dumb and idiotic. I feel wretched and get weary, worn out after a half-hour of this torture, but of course, it goes on for hours, not minutes. By the time a visit is over, I am wrung out. My consolation is my books and the love of my wife, children, and grandchildren. At home I can withdraw into the world of literature, and I can participate in the contemporary world through my love of baseball and by exercising my voting rights. This is what I am reduced to by the COVID-19 pandemic and my hearing impairment: an attenuated life of incomprehensible noise and social isolation.

Julia C. Spring, New York City, New York

Journal entry, May 10, 2022

I didn’t miss museums, concerts, plays during the first pandemic year and a half. I don’t really know why not — maybe it was like Stockholm syndrome, identifying with Captor Covid and forgetting that I used to be out in the world. Or maybe I reactivated an old defense and didn’t let myself want what I couldn’t have.

But now that I’ve started doing things, my heart is hungry.

Last Saturday it was pouring and I decided to see an exhibit, someone I hadn’t heard of before, Hilary Pecis, whose works looked to be big, bright and detailed, just what I needed.

I got drenched on the way to the car then drove to the gallery — there 45 minutes (yes, big, bright and detailed) keeping my distance from the few other people — soaked again walking back to the car, drove home — changed out of my cold wet clothes and stayed inside for the rest of the gloomy day.

I felt radiant from my adventure, as though I were the sun and it was soaking into me.

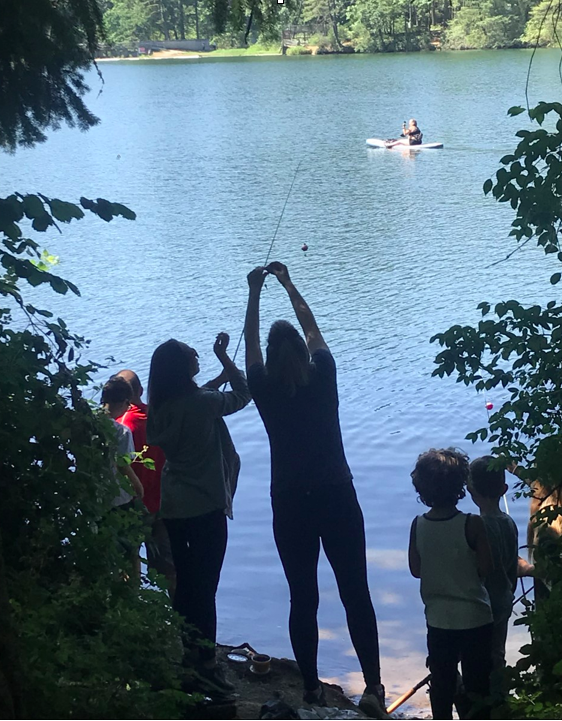

Mark Tochen, Camas, Washington

Journal Entry, June 7, 2022

The Fourth of July, 2022 approaches. Let’s contemplate the Fourth of July celebration we might enjoy if Covid truly eases in our lives. We could then shout with joy, here comes the Fourth! All through the land there will be a Fourth of Joy as well as a Fourth of July. We’ll go to the park on the lake near our home for day-long picnics and play. We’ll preen and pose for pictures, kayak and paddle board and go fishing in the little lake, and take an easy two-mile walk around its rounded contours. It’s not really a swimmable lake — algae count is too high — but it’s very pretty with green trees all around, their reflections shimmering in the water. We’ll be like Bilbo and Frodo playing in the Shire, and the sun will rise high over our pleasure. Every face will be unmasked so we can delight in all the smiles of happiness and relief at our freedom. No more sheltering in place, and little kids will race around finally free to move and dance and mingle. We won’t even need fireworks, we’ll be safe and our joy will provide fireworks sufficient to gladden our hearts. It will be the Fourth.

Isabel Soto-Garcia, Madrid, Spain

Journal entry, June 7, 2022

I have a life-long passion for pre-used stuff. Pandemic restrictions have limited my rummaging for recycled treasures in second-hand stores. And yet I’ve taken a quantum leap towards conservation: I’ve installed solar panels on my roof. Or rather, several young men, sweating heavily, did.

A two-day job, the company said, and the installation would be “external” as a mobile platform charmingly called a cherry picker would lift workers and panels onto my roof.

I felt righteous.

Frustration replaced the righteousness. Five workers, strangers to my personal pandemic bubble, entered my house on day one and walked up the three floors to access the loft and my roof via a small window. Maskless. I guess “external installation” was poetic license.

I’m a cancer patient, always masked up in indoor spaces and in the company of strangers, however kind. I politely asked them to mask up.

“We have no masks,” they said.

“I’ll give you some,” I said.

Day two. Three workers today. Maskless.

“Stay in your office,” says my (masked-up) husband.

My confinement lasts twenty-seven minutes.

“I’m about to explode,” I text my husband.

“I’ll email the company,” he answers.

The company’s apology is lukewarm: anti-covid measures have been eased, guidelines are confusing . . . My husband asks the guys to don the masks I’d laid out for them the day before. They comply.

My solar panels are now in place. We draw energy from the sun.

Covid is still here.

Ageism and sexism are still here.

I am still here.

Judith Shapiro, Washington, DC

Journal entry, June 3, 2022

Mother’s Day this year was amazing. Several months ago, I couldn’t have imagined life outside my cocoon. Then, I was dealing with long-Covid. I had a false sense of functionality that served me well. Maybe not well, but good enough. Most mornings I put on the same clothes, went directly to the computer to join zoom groups throughout the day. On good days I walked on the beach. Also, on good days I forgot that good days were scarce. My daughter, Julia, said I had the memory of a goldfish.

Then, there we were, Mother’s Day, Kristara, Jerzy and I, out in public. We got lattes. We strolled on the common. We went to the movies. The first time in over two years! Later that night Jerzy started feeling sick. The next morning, still not well, she tested positive. My heart sunk. Surely I didn’t catch it again. Five days later I pulled out a test kit, reminiscent of at-home pregnancy tests I used years ago. I watched apprehensively as the control line became solid red, the test line thankfully blank, the opposite of my hopes from those other tests in the past. Gradually the line morphed into a faint, ghostlike grey. I called Julia to let her know. “So sorry,” she said, “but on the bright side, you’re in good company. I bet a lot of moms got it for Mother’s Day this year.” The bright side indeed.

Stephen Kingsnorth, Coedpoeth, Wales

Journal entry, May 25, 2022

Each Friday is my dancing day. Who could have imagined, the diagnosis, a flyer passed, then weekly Zoom, “Parkinson’s Dance,” alongside twenty others, with English National Ballet? We follow moves seated or standing, prance classical, contemporary, in fusion choreography. I pas de chat, plié, rise, hold armchair wing, and arabesque in overweight. I even write a verse for print at seventy, as ‘body movement’ is the theme, with photograph, screen, my balanced belly hanging there. We break out, reminiscence time, and share our wonder, what we have achieved.

Patricia Cannon, Novato, California

Journal entry, October 20, 2021

“Great necessities call out great virtues. When a mind is raised and animated by scenes that engage the heart, then those qualities which would otherwise lay dormant, wake into life . . .” Abigail Adams’ words are fulfilled every day by my therapist and those like her — the brave-hearted who work behind closed doors. Therapy supported my ability to function as a nurse during the pandemic. Lack of sleep and the increased demands on my mental, spiritual and emotional reserves hurled me into the survival mode of “fight or flight.” Even though I appeared calm: I had some form of PTSD. My hands couldn’t stop shaking. During this time, I had to reassure my patients that another nurse would insert their intravenous access. My therapist used visualization and cognitive behavior techniques to assist me through the workday. My hands are now steady, and although I wouldn’t say I am a “vein whisperer” like my boss, I can hold my own again. Sadly, many seasoned counselors and therapists have left their professions due to unprecedented stress. Thankfully, my therapist is holding fast. I think of all her clients and the “worlds” she inhabits each hour. The living condition on each varies with each client, yet she keeps showing up for us despite the climate.

Jennifer Schneider, Dresher, Pennsylvania

Journal entry, May 28, 2022

on shedding, molting, and re-engaging :: observations on the maskless

some mammals shed fur. other animals, reptiles such as snakes and lizards, shed skin. growth a life-long process, typically one of renewal even while simultaneously unsettling. snakes and lizards experience diminished appetites. molting processes equally meandering. anthropods such as crabs, lobsters, insects, and krill transform. growth always pressing. time always splitting.

homosapiens shed, too. two times twelve plus two — no, three — months into the covid-19 pandemic and masks are starting to shed. sporadic, increasingly present, moments of exposed flesh. skin as viral as tweets. flashes, of sorts. amidst blinding light of camera clicks and warmth of crescent-moon smiles, a list of unexpected encounters. handkerchiefs both ready and revealing. less a time of renewal than renewed anxiety. similar to the anthropod. a time of vulnerability. plus a sprinkle of unmissed/can’t miss traits.trials.tribulations.

1. Jawlines sag as COVID rates ricochet.

2. Aging operates differently above and below lip lines.

3. Lips thin as waistlines expand.

4. Masks protect against multiple transmissions.

5. Unwelcome pecks on cheeks wage new wars.

6. Grins reaffirm gripes with tooth-filled greens.

7. Viruses rebound on the week’s starting line-ups.

8. As COVID rates fall, social awkwardness rates continue to rise.

9. While Cupid’s bow is a sign of beauty and delight, some bows (and bad breath) bite.

10. Soft whispers ebb & flow with new waves. Souls struggle to ride them to shore while labs run trials, squash loops, and lob lifeboats.

Ellen Campbell, State College, Pennsylvania

Journal entry, May 14, 2022

I have long been a knitter – making socks, sweaters, shawls, mittens, gloves, hats and more for family and friends. The rhythmic cadence of my needles helps me unwind each night, offering the calm needed to end even the most stressful day. But during these past pandemic winter months, my knitting needles no longer call me. Something seems out of kilter inside me that even knitting can’t make right. One day last month, I picked up a needle of a different kind.

Thread of a different kind. I cut up cast-off fabric and orphaned quilt blocks and just started stitching simple lines, squares and circles. These little thread doodles are turning into soft books filled with writing of a different kind, creating a new way to shape an ever shape-shifting world. One stitch at a time.

MaureenTeresa McCarthy, Canandaigua, New York

Journal entry, April 28, 2022

An Island Garden, by Celia Thaxter, is my respite in this never-ending pandemic. I have read it, paged through it, lingered over illustrations. My copy is a reissue of the 1894 edition with color lithographs by Childe Hassam, who was foremost book artist of the time. The book, the paintings, the garden, Thaxter’s life, her writing, all give me deep comfort.

The garden is the focus of the book, a colorful living tapestry Celia Thaxter designed and brought alive every summer. She writes of deep pleasure in the flowers and wildlife of her island home. She writes too of loss as storms ravaged flower beds, destroying her work. She planted, pruned, transplanted, over and over, but she was well aware that nature is capricious. Winds, waves, rains are far more powerful than a gardener. Viruses are too.

Her life’s work reminds me that this split world we live in now will heal, as nature does. Our lives will change, but we can restore, redesign, replant, as Thaxter did, many times.

Elaine Logan, Baltimore, Maryland

Journal entry, April 21, 2022

While dusting my small collection of art books, I noticed one in particular: The Girard Collection at the Museum of International Folk Art. I laid it on the buffet. It fell open to a two-page spread of tiny, unglazed-ceramic figures of a crèche. But it was a whole village, perhaps 24 figures and even more animals, paying homage to Mary, Joseph and baby Jesus. I must have studied it for many minutes and decided I’d study each page one a day – until I had gone through the whole book.

That led to making a thing-to-do of all the art books I had. Books that were treasured but seldom brought out simply to enjoy. The posters of Hockney and Klimt, the architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright, the designs of Cranbrook and Charles Rennie McIntosh, the paintings of Carl Larsson – each had their day – actually, it was more like a month.

Finally, I took out a historical atlas that I needed to see where in Europe the Czech Republic was before the First World War. That led to finding A to Z maps from England, and eventually a more contemporary world atlas so I could figure out exactly which countries of Europe abut Ukraine. And where is Mariupol, and why is that seaport so critical to Russia?

All this gave me a way to use huge blocks of time, and the peace and calmness that comes with looking at long-lost treasures, understanding them with eyes of age, and appreciating them anew.

Ronald W. Berninger, Baltimore, Maryland

Journal entry, April 21, 2022

When my wife and I retired to Roland Park Place, we brought many books we had not had time to read when we were so busy with our jobs. During the pandemic we read most of these books. We also spent time listening to all the music we had collected over the 50+ years Ginger and I have been married; we played the VHS tapes, vinyl albums, CDs, and DVDs again.

When residents could finally leave Roland Park Place if they wore masks and practiced social distancing, I made a big effort to start and drive my 2014 Ford Fusion Hybrid at least once a week for 30 minutes or more on the interstate at 55 mph. This was done to keep the battery charged up completely and have all the vehicle fluids get up to operating temperature. Also, it was therapeutic to get out of the apartment, and we enjoyed the scenic trips along routes 83 and 695 and side roads.

Martha Strom, Brooklyn, New York

Journal entry, April 24, 2022

These are the first flowers I have bought myself since COVID began – it was a sheer joy to try to paint them. I do love to write, but painting flowers fresh from Trader Joe’s filled me with incomparable bliss.

Diane Payne, Holland, Michigan

Journal entry, January 2022

My first winter back living in my hometown after four decades, our country ends up in a lengthy pandemic, and I didn’t remember the winters being so long, so dark, especially with our state in a long lockdown. The house is just my cat, dog, and I, and all my plans of potlucks and happy hours squished inside my small house have transformed into sitting outside by a fire with a few loyal friends who are now a “pandemic pod.” My days are filled with long walks through the dunes and along the lake, waiting for the icebergs to form and this damn pandemic to end.

Lois Villemaire, Annapolis, Maryland

Journal entry, December 1, 2021

This has been a stressful two weeks. Paul has improved greatly, thank goodness. Was it the monoclonal antibodies treatment or the normal relenting of the virus? We don’t know but no matter, he is doing better. And so far I have remained unscathed. When my PCR test came back negative I was amazed and relieved.

We are wearing masks and have not been sleeping together. During the day we operate in different parts of the house. Today is Saturday. What difference does it make what day it is?

Yesterday I cleared out all of the fallen leaves in the backyard. Some had gotten into crevices and piled up deep against the house and fence. The wind was to blame. The yard is small with many pesky dead leaves and looking it in that condition was depressing. Filled with nervous energy, I armed myself with a blower, rake, and snow shovel. Yes, a snow shovel helped with getting the huge pile of leaves into the woods. I spend so much time writing at the kitchen table these days and the yard is my view. Improving my view was the impetus behind taking on this dirty job. It looks so much better. I still have to get rid of dead plants to ready the yard for winter.

Roberta Schine, New York, New York

Journal entries, March 2020 and March 2022

Rosie and I call each other a lot. It’s been that way for the fifty-plus years we’ve been friends. I almost know the sound of her ring. “Hey Rosie, what’s up?” I ask. “I just got back from the store,” she says. “I burned my clothes, took a Silkwood shower, threw the bag of groceries down the incinerator and douched with Clorox. I’m good.” We laugh, each knowing the other is scared shitless.

The next morning, we meet at the usual place to walk. The corner of East 14th Street and First Avenue is exactly mid-way between our apartments. We don’t make changes because of our memory issues. Rosie immediately takes a 6’ piece of string out of her backpack and explains that she brought it to help maintain social distance. She tells me I’m a “drifter.” So, we hold the string taut between us and begin walking towards the East River.

Having a conversation is difficult. For one thing, we’ve both noticed some hearing loss – mostly, each other’s. Masks don’t help; we sound muddled. And then there’s the ambient noise. Empty buses clang past and there are a few screaming babies on the street.

I ask Rosie to speak up. She yells, “I’VE BEEN CONSTIPASTED ALL WEEK. NERVES.” I say, “Look, maybe we should just think of these walks as a Zen meditation. How about if we’re quiet together and then call each other when we get home?” We try but that doesn’t work; we’re both pretty chatty. Then, I remember my brother’s suggestion to use our phones. It’s a struggle to dial Rosie’s number without removing my surgical gloves. After a few mistakes, it rings and she answers from across the sidewalk. “Hi Rosie,” I say.

March 2022

Last week a sprig of green peeked through the snow at Tompkins Square Park. Now, Red-Tailed Hawks congregate and tend to their enormous nests. Rosie and I have our N-95s on under our chins. Rosie looks good. I realize I haven’t seen her smile much since her brother’s death last summer. We gaze at two headlines on the front page of the newspaper she just bought: “Covid cases down in New York City” followed by, “New Omicron subvariant, BA.2, is circulating in the US.” We try to process these two disparate facts. Finally, I say, “I think the daffodils are coming up. Shall we find out?” We link arms, pull our masks up and go in search of the pretty blossoms.

Mary Wasacz, Scarsdale, New York

Journal entry, March 18, 2022

During the Covid-19 lockdown, high tension abounded in our home between my husband, John, and Gracie, my umbrella cockatoo, who squawks in ear-piercing sounds. Gracie is all white except for the undersides of her wings and tail which are yellow. When happy, sad, or scared her crest opens up like an umbrella.

John is writing a book from home while on sabbatical. “I can’t concentrate with all her noise,” he says. After a few days of this, John exclaims, “If Gracie doesn’t stop, she’s got to go. I have a deadline to meet.”

I slam my book on the table. “That bird isn’t going anywhere.”

The next time she squawks, John goes over to her. “What’s your problem?” Gracie quickly goes to the other side of her cage, looks at John and then slowly comes towards him, throwing him kisses.

“You calmed her down, John.” He smiles, beaming with pride.

“I’m a good girl,” says Gracie.

She gives him more kisses and does her tumbling on her rings. John gives her a pine nut. Later when John walks into the room, Gracie says, “Hello John.”

Pia Wood, Henderson, Nevada

Journal entry, March 19, 2022

Home from the first concert in two years. In bed humming that tune from years ago. I can’t sleep. I just think: We have escaped from the quiet of the Pandemic. We have arrived from the Pandemic shedding our mourning dark blue, black and gray moods. We have pierced the shield of the Pandemic while moving fast, running hard, and jumping over new hurdles on a dare of finding joy. We have danced away from the Pandemic leaving the slow drag behind. We have twirled away from quarantined corners. We have shifted gears to speeds that affirm: life is short. The lifting of the mask mandate offered new color in a world we thought black and white. Yet, our hearts know that at any moment the universe can install barriers that reveal themselves in slow motion. Tonight at the concert bold and muted colors floated around me as I shimmied and bounced like I did at my high school prom. Tonight, I double-clapped my hands like a genie granting the world’s wish to make the sorrowful Pandemic memories disappear into the boogie of the music.

Maureen Murphy Woodcock, Cathedral City, California

Journal entry, March 18, 2022

It’s been over 45 years and I believed I’d successfully banished a repeated nightmare that haunted and tortured me for weeks. But it’s back again – resurrected with this war in the Ukraine. Social media and the news networks have posted stories and pictures of young mothers – like I once was – with their handicapped children. Some of the kids have multiple, severe disabilities; meaning they are non-ambulatory, unable to feed themselves, or unable to talk.

In the mid-1970’s, an older woman from Poland lived next door to us. She told me about how she’d fled Warsaw when it was under siege during WW II. She looked at my three children and said how lucky I was to have never been forced to escape an invading army. “You wouldn’t have made it with her,” she said, nodding at my 7-year-old daughter, Erika, who had multiple handicaps. The woman patted Erika’s wheelchair handles. “This thing is worthless. You can’t push it over rubble, up mountain paths, or across rivers with no bridges.” My neighbor sighed. “War means you’d have to make terrible life and death decisions. Go or stay? Would you abandon Erika? Just take only your other two children who would have a better chance of surviving?”

But I didn’t feel lucky. Her words crept into my sleep. And I wondered if my neighbor was telling me her story. I didn’t have the nerve to ask her. Night after night I worried about what I would do if my world was suddenly bombarded. It never was and, eventually, I felt fortunate and blessed.

Since then, Erika has passed, and her older brother and sister have safely reached middle-age.

For years, my terror of how to flee a war was forgotten. Until Ukraine happened. Once again, I didn’t sleep well. Still didn’t know what to do, how to help, or how to make the world we live in feel safe. But today I woke up, ready to pitch in. I won’t let nightmares paralyze me. If I inhale slowly, take deep calming breaths, there are many things I can do; contact agencies like UNICEF, Doctors Without Borders, The Ukrainian Red Cross, Nova Ukraine, Project HOPE, Save the Children. I can contribute my air miles to refugees.

This morning, I phoned friends in Poland and told them how proud I am of them. I asked them if there’s anything I can do to help. These wonderful friends have given some Ukrainian mothers and children the unlimited use of their vacation home outside of Warsaw.

Taking action, even tiny steps of action, has infused me with hope.

James Higgins, Eugene, Oregon

Journal entry, March 1, 2022

My state of Oregon will lift its mask mandate at 11:59 PM on March 11th. The only places then requiring masks will be in health care settings, public transit and airports.

I am 81; my wife, Anne, is 77 and spent the last year being treated for an aggressive form of breast cancer. The treatment involved surgery, 15 weekdays of chemo therapy, oral medications and a number of infusions. Now, she is cancer-free, we are told, but will continue taking an oral medication, getting frequent mammograms and visiting the cancer clinic every month or two. Of course, her immunity system is still compromised. I am mostly healthy, only one prescription needed.

Our dilemma then is this: It seems to me that we should continue to wear masks for at least the immediate future. How long? That is the question we will be asking her Oncologist. I will continue to do most of the grocery shopping and prescription pickups and I will wear a mask to protect Anne.

Elaine Lambert, Montoursville, Pennsylvania

Journal entry, February 22, 2022

2-22-22. Twos in sequence. Angel numbers, signifying an awakening. Expect messages on this day, February 22, 2022.

Yesterday, I went into a store without a mask for the first time in two years. It was a rare sunny day. I wanted to breathe the warm air, wear lipstick, see facial expressions. I wanted to feel connected. Going mask-less felt like a risk I needed to take.

In the early months of isolation, keeping busy was how I distracted myself from loneliness. In this period of hyperactivity, I constructed a complex little quilt based on a pattern by Cheyenne Goh: Ring of Roses Mandala. Winding long, cut strips of fabric into tight circles assembled into larger rings, I formed a three-dimensional, 20-inch circle unlike any other quilt I’d ever made.

My quilt mandala reminds me of “Ring Around the Roses,” a song once claimed to be a historical remnant from London’s Great Plague of 1665. Experts say that is false; the story is meta folklore (folklore about folklore). In fact, it is just a dancing game traced back only as far as the late 19th century. The “ashes, ashes” do not describe mass cremations (illegal in 1665). When the dancers “all fall down,” they are not recreating black death scenes from any century. They are bowing to one another to mark the end of the dance.

Could the end of the Covid dance be the blessed revelation of 2-22-22? I remove my mask and bow.

Susan Fealy, Melbourne, Australia

Journal entry, January 30, 2022

When is a sunset the beginning of a story? In writing this, I suspect that I have my answer. You see, the sunset was so vivid, its feathers were made for a bird not yet invented. But even a potential bird needs a cage. I rushed out into the side street with my camera, and there were two young people up on their roof in glorious silhouette. I felt like shouting out to them ‘touch the sky for me’. I settled on a wave. The young woman waved back, then turned to the young man by her side. So I caught them instead. A great snap of roofline, young lovers, and that bird. I left them a note asking if they would like my snap of the sunset: them in silhouette. Silence for five days. Then an email. She had just got my note. They had been isolating. Her flat mate has COVID. I sent them the snap, offered to shop. Now I have an invitation to partake of their greens. The pandemic has broken some boundaries. And some birds have not yet been invented.

Alan Bern, Berkeley, California

Journal entry, February 10, 2022

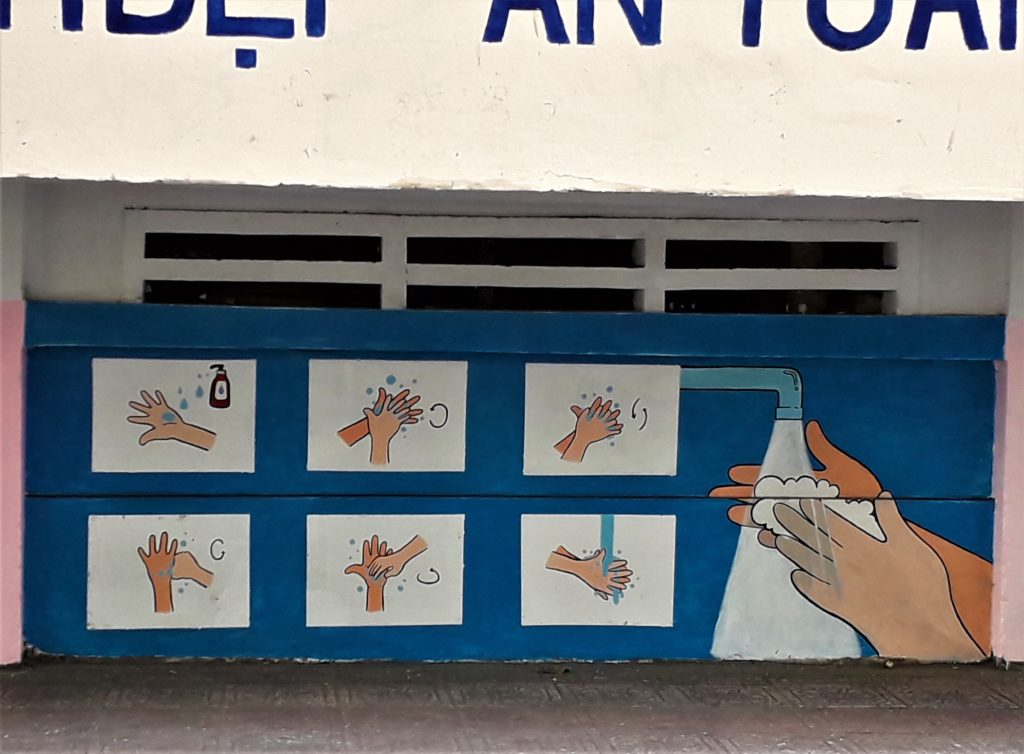

Under and pressure fit together, good mates, perhaps even mating, although, when apart, each flees in many directions. Under pressure, the phrase itself is. Deep anger here and abroad, and our job is to remain tactical, compassionate, brilliantly under pressure. There is fear abroad and beside us. Some pronouncers speak with deep compassion challenging the deceivers and the viruses themselves. “Wash your hands.” Perhaps instead of singing “Happy Birthday,” songs of fearlessness.

Inevitably some sicken and will need treatments: when they arrive in responsive hospitals, they may be greeted by the tongue depressor, miraculous instrument, probably first used during our first U.S. Civil War. The modern one, perfected by Jerome H. Lemelson, 1923-1997, who first conceived of a tool to hold down the tongue to examine both tongue and throat: he made a metal one for his physician father. Because metal ones are so difficult to clean, better a simple wooden one, disposable. Work, flat wooden flap! Now you are needed more than ever before.

Under pressure from this fine tool, tongue depressor, much revealed. Some patients may gag, but do not worry about gagging: inspections are brief — all will surpass, whether our exact world ends now or in 10,000 years. There will be suffering and suffering. Only vast compassion can alleviate some suffering.

Cynthia Dorfman, Rockville, Maryland

Journal entry, February 20, 2022

The roundness of sand grains, the round of snowflakes in the rounding of time: history repeats itself with the same symbols, but in different ways. I counted snowflakes instead of sand while waiting. This is how I felt then and now feel again after 60 years — points of transition. Coming home from a long-postponed visit with my daughter in San Diego, I brushed sand from my coat and cleared snow from the car at BWI Marshall Airport in Baltimore. The pandemic has lingered, and all I can think of is the waiting. At first, I thought the shutdown was like a school closing after a blizzard with anticipation of a sledding holiday. Instead, the pandemic has lingered, cabin-fevered for two years. How can I cope with this waiting?

The only memory I have of such a lengthy time span was over the two years anticipating my father’s return from a tour of duty in Okinawa with the Marines. It was the dawn of the 1960s and the beginning of my teen years. We had been forced to move from Camp Pendleton’s sandy hills to my grandmother’s icicled Victorian house at the foothills of the Adirondacks.

Waiting during those two years taught me patience in the fog of fear — fear for my father’s life and safety. Now, over two years of the Covid pandemic, I have sat in fear for my children and grandchildren’s lives and safety. Once again, as I experience my seventh decade, it has been a time of counting snowflakes instead of sand. I am waiting for the snow of the virus to lift so that I can once again feel the sand slipping freely through my hands.

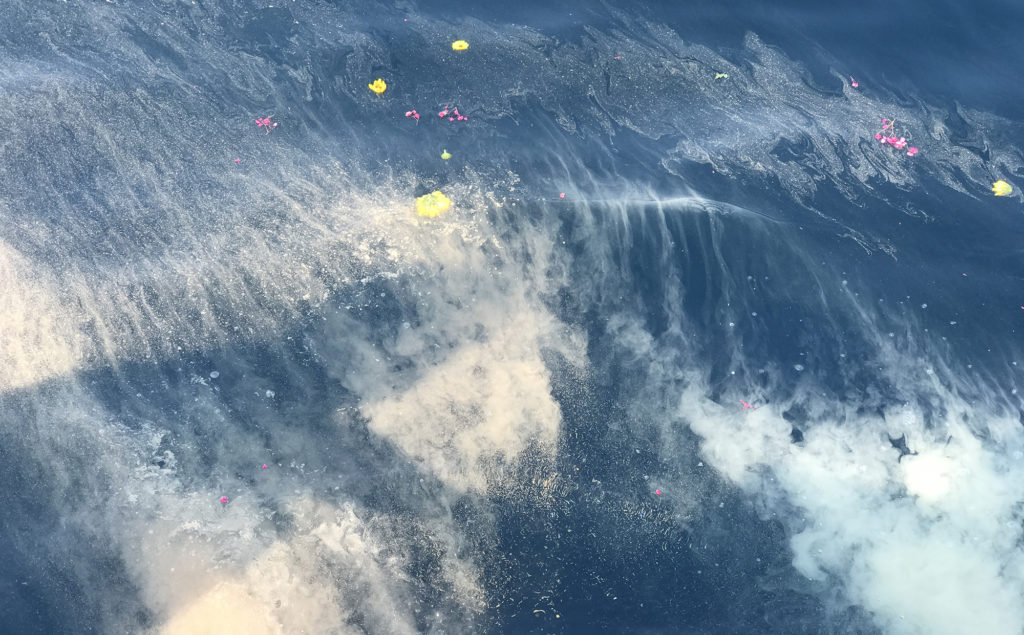

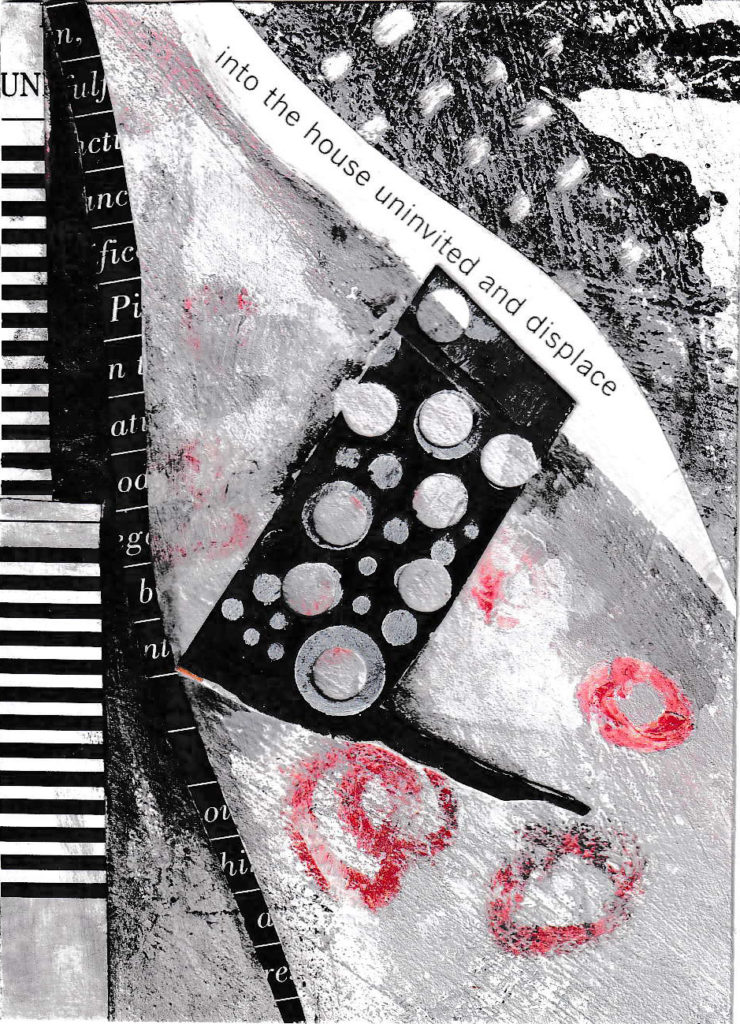

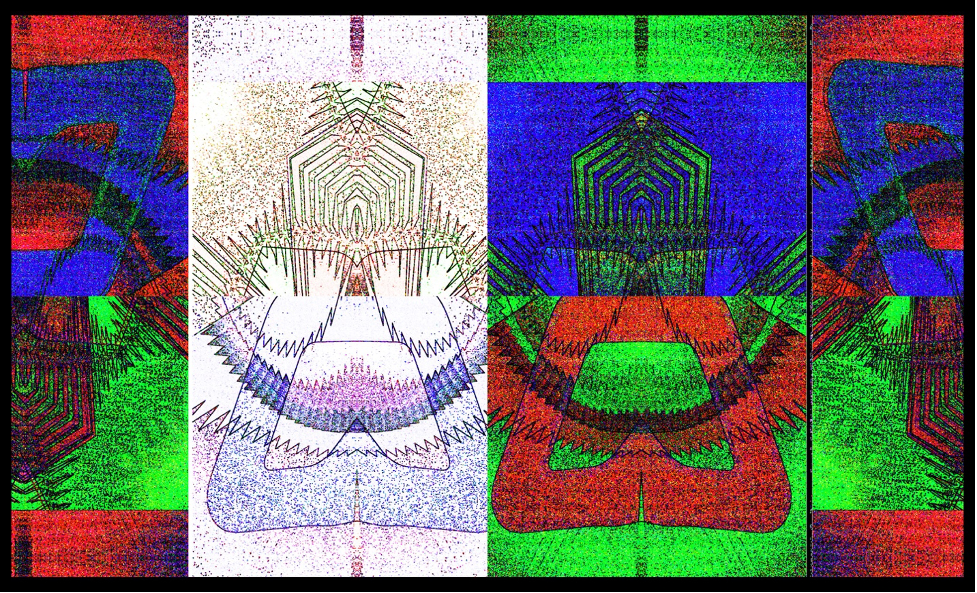

Jennifer Pratt-Walter, Vancouver, Washington

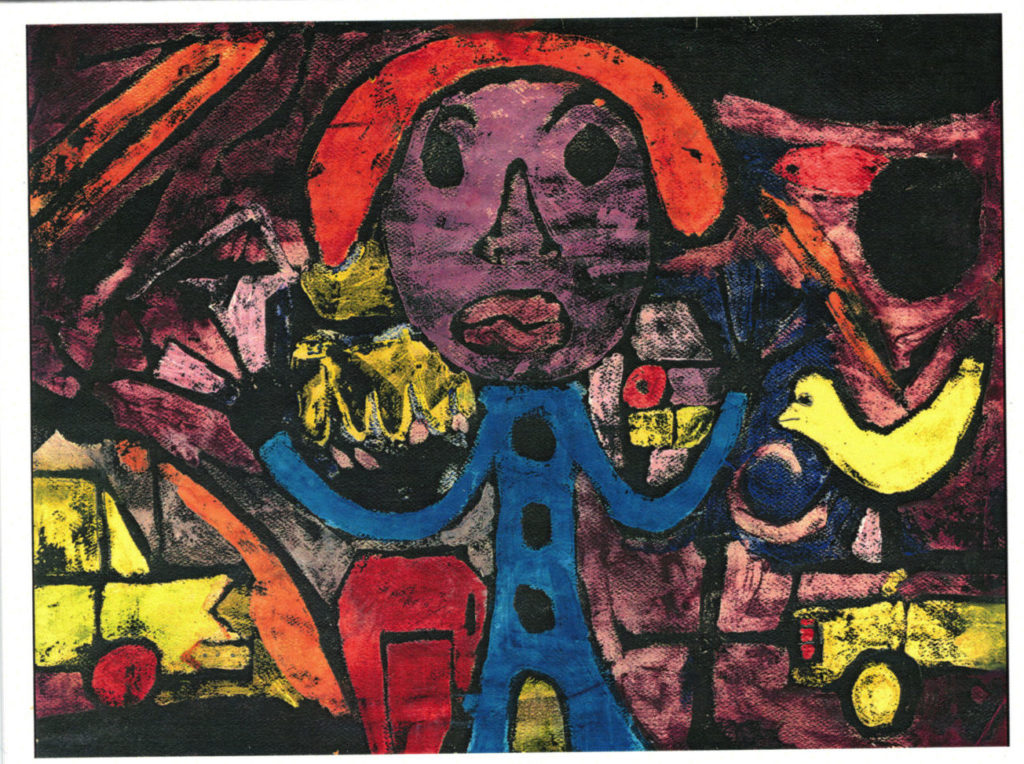

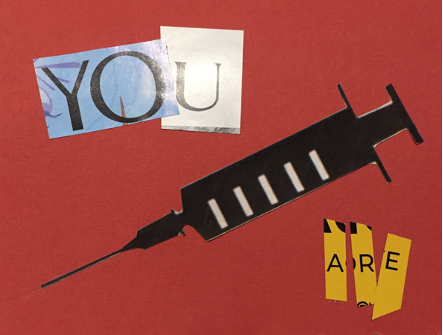

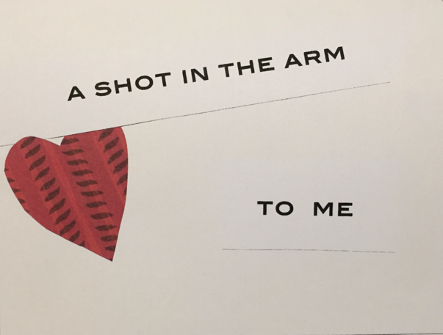

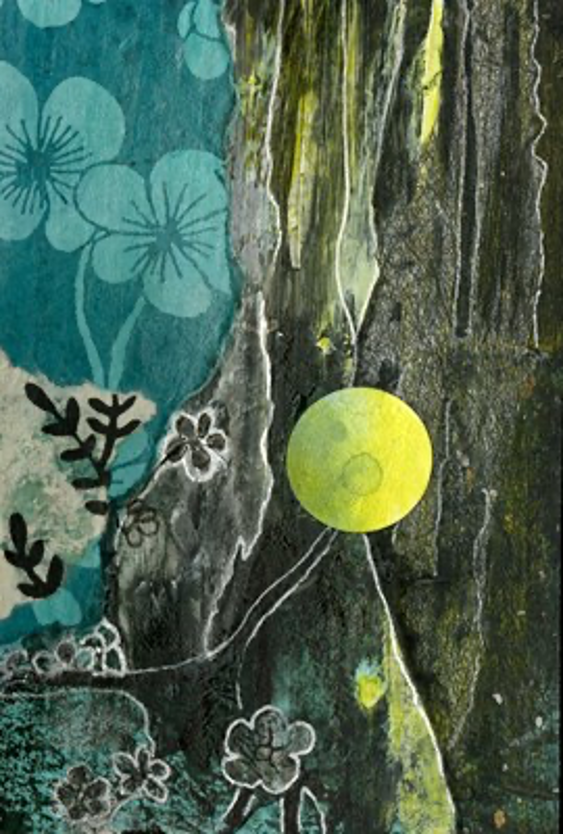

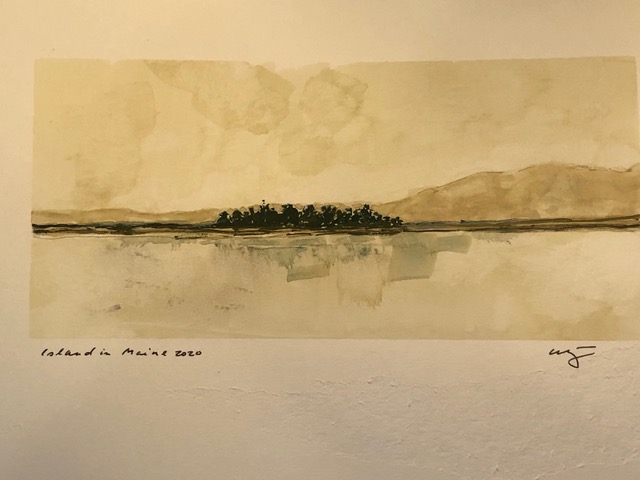

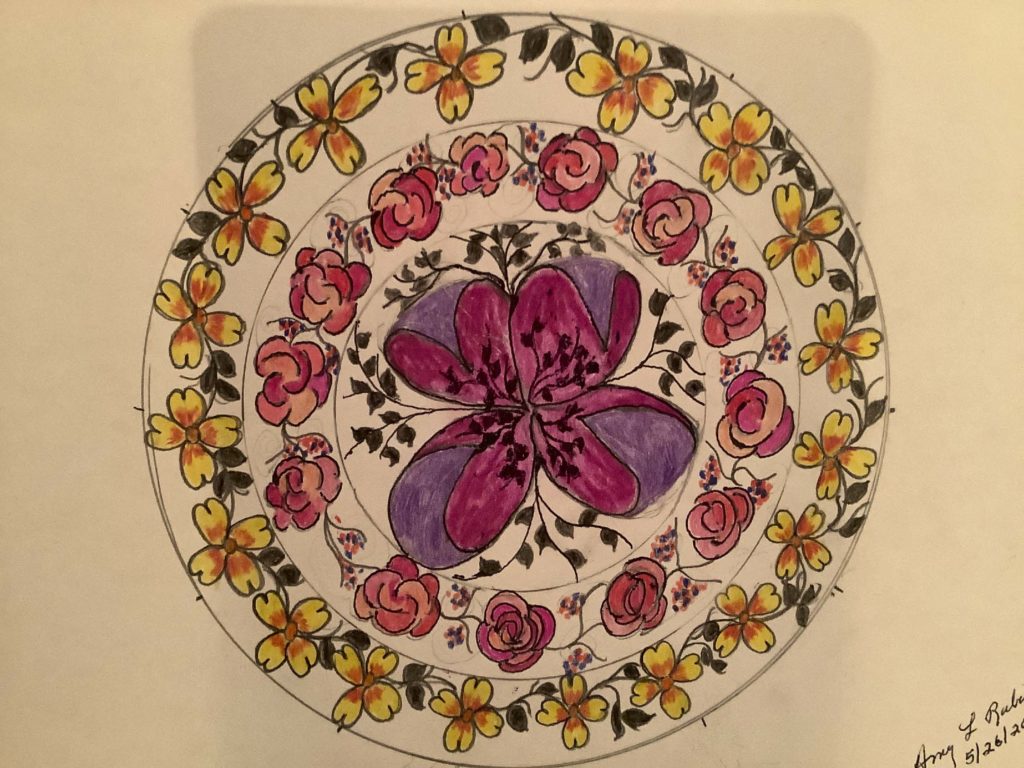

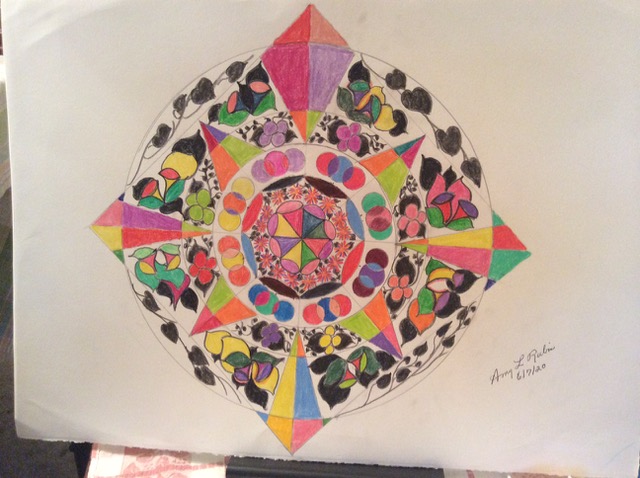

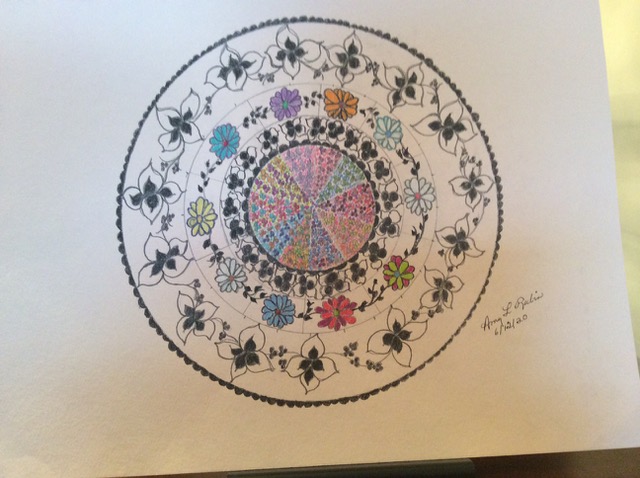

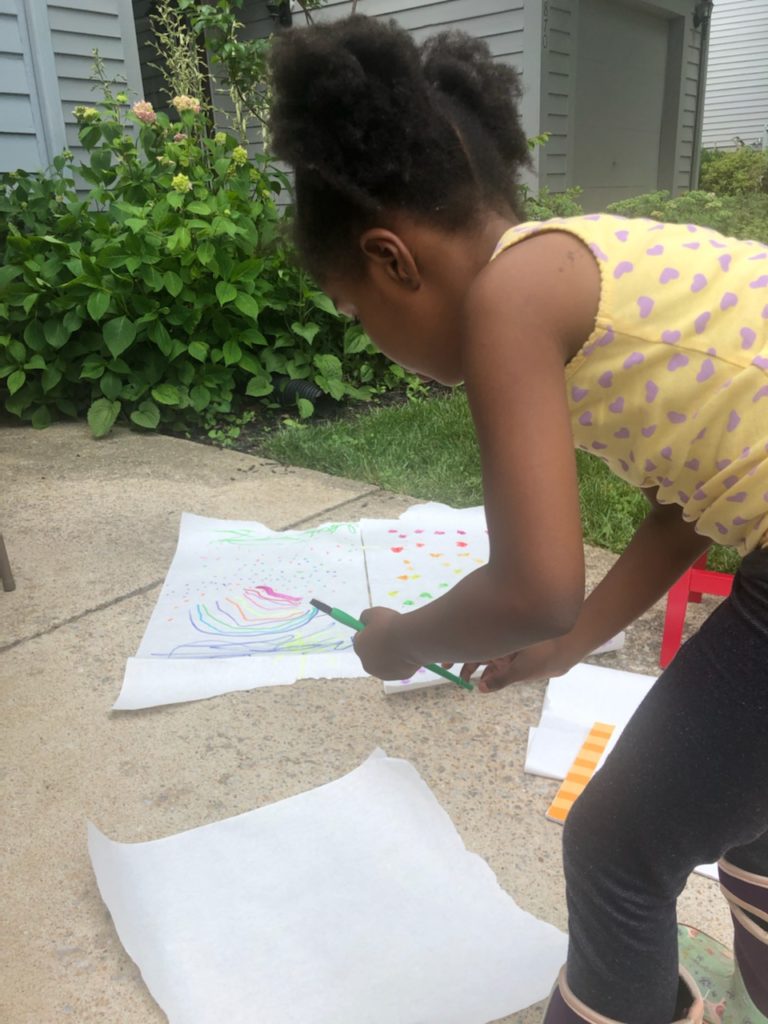

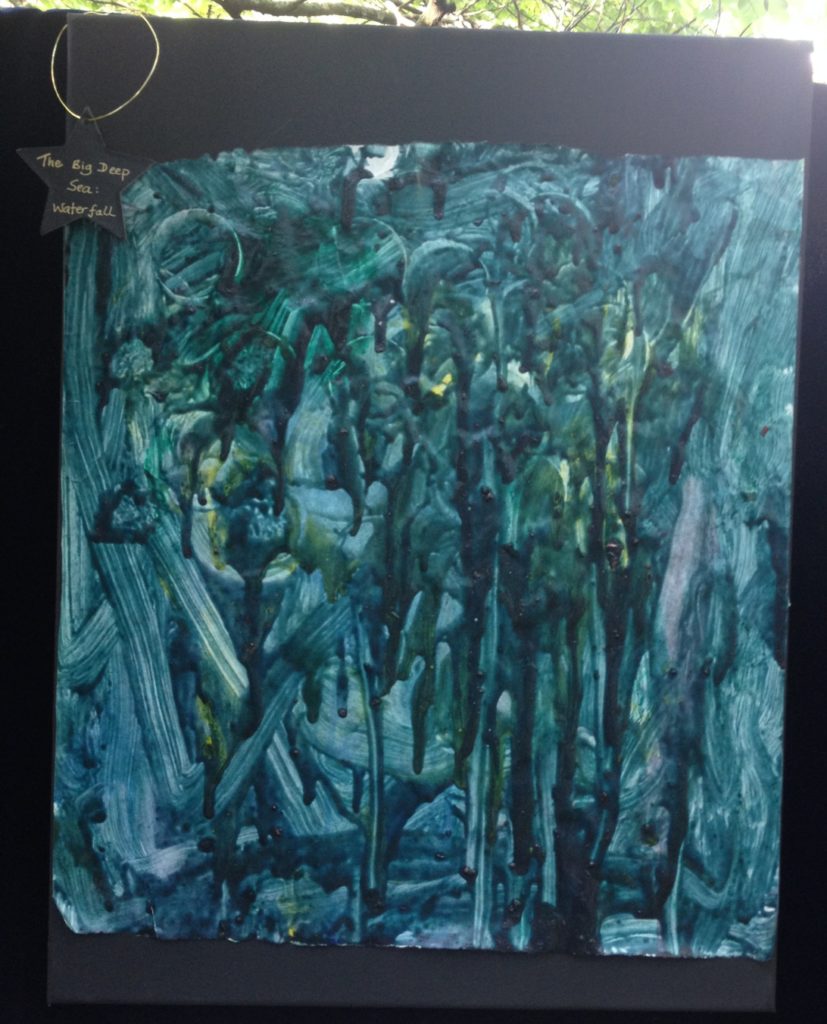

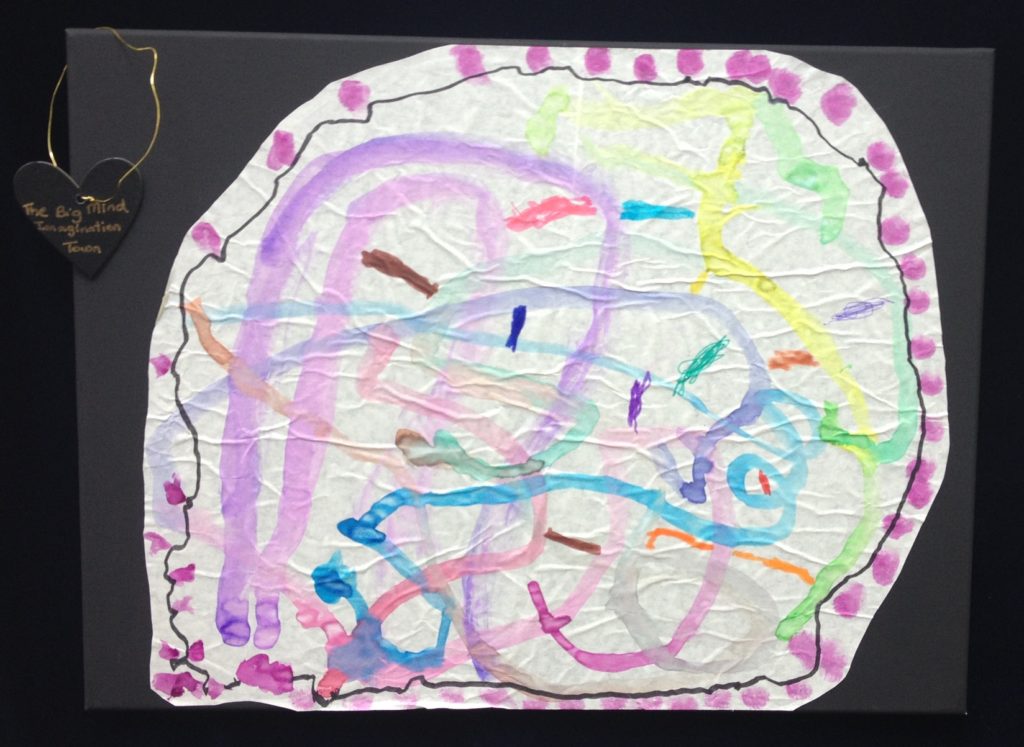

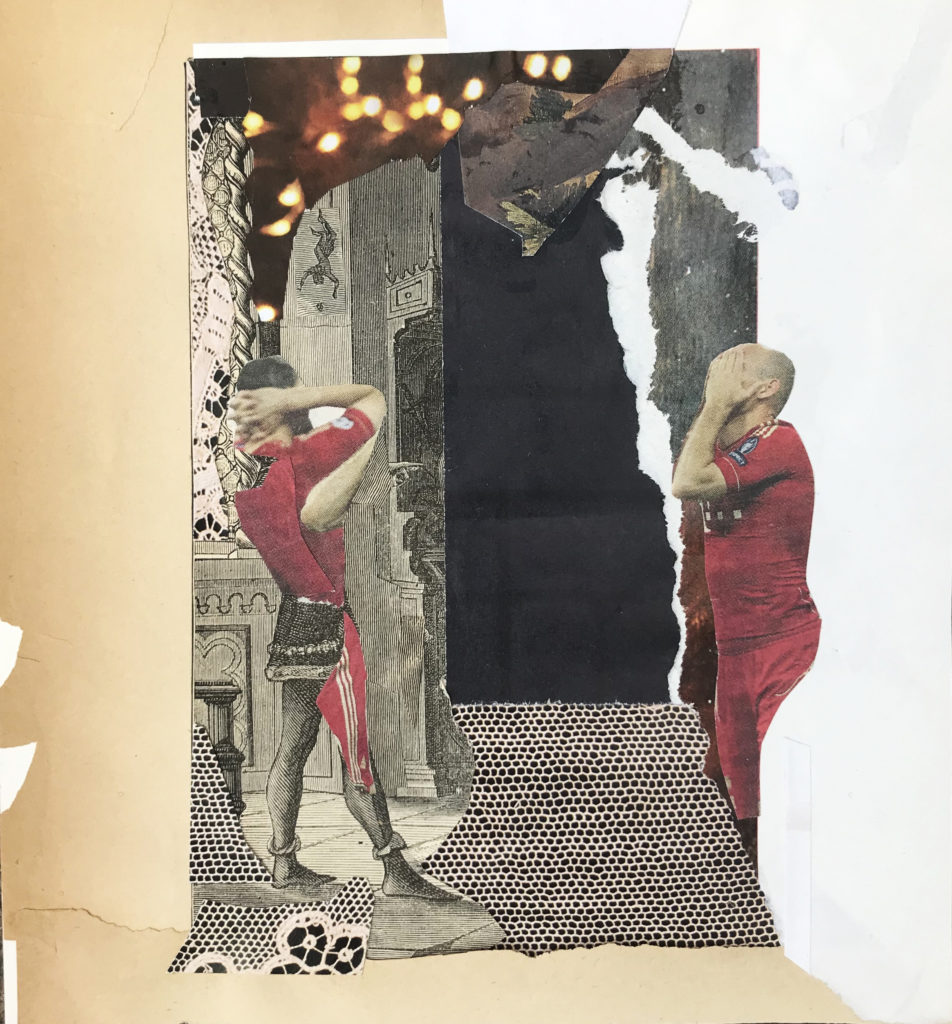

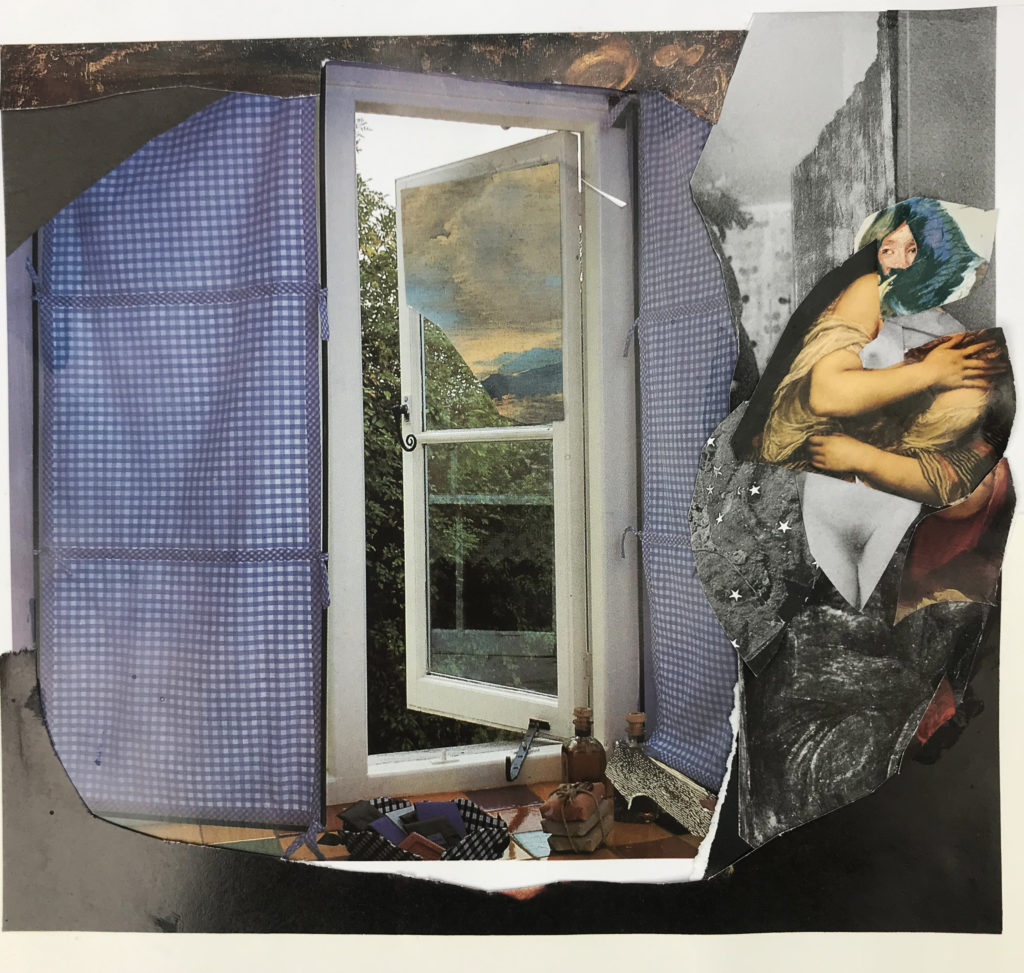

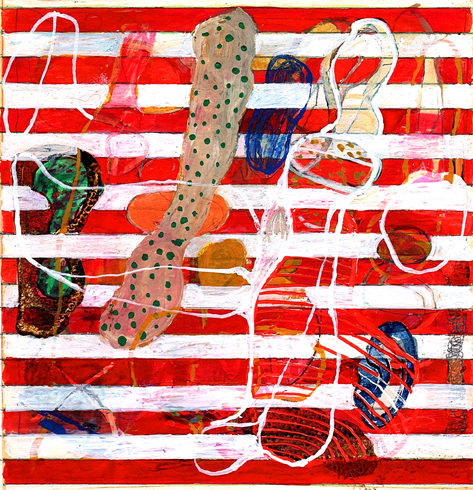

Art entry, February 18, 2022

The images are based on a deep sense of hope that is embodied in delicate living beings. The hope ringing in my heart is both for healing and recovery through the pandemic and for spring opening its very welcome door.

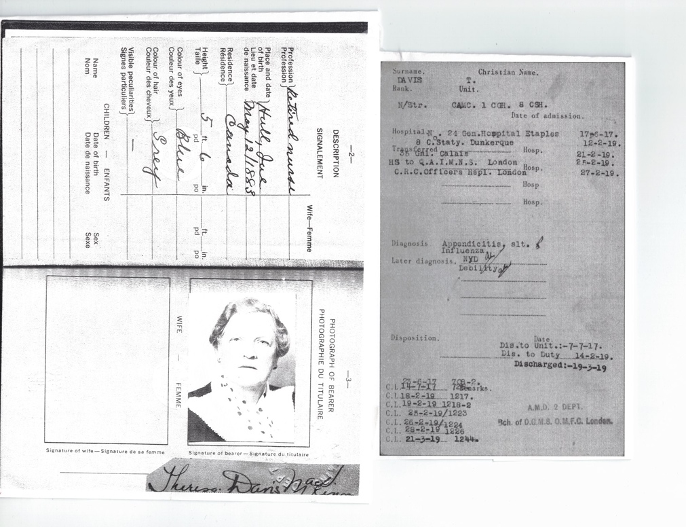

Joel Savishinsky, Seattle, Washington

Journal entry, February 16, 2022

Today would have been my parents’ 81st anniversary, and while gazing at their World War WII-era wedding picture, I look to the right at the photos of five people they never got to meet . . . their great-grandchildren. Thinking about those generations in our third winter of Covid, I wonder about the medical crises that have marked their time in history. When my parents were children, they lived through the 1918 flu epidemic. Yet I never heard a word from them, or their parents, about that world-shattering illness. Their reticence, if that’s what it was, has always mystified me. Yet it is of a piece with the silence of our culture at large, whose literature, films and art have rarely dwelt on that traumatic, frightening period. It has taken Covid-19 — the great-grandchild of the 1918 virus — to remind us of that time and urge us to try to re-learn some of its lost lessons.

Looking at my parents’ faces, I ask myself: what were the fears they lived with as young parents. In the 1940s and 50s of my own childhood, my mother and father had experienced the defining pandemic of their adulthood: Polio. Born in 1944, I would develop mild symptoms at age 10; my older cousin David was stricken with a serious case of polio just a week before his Bar Mitzvah; and my wife Susan, born in 1945, would — as a four-year-old — end up in a special hospital ward, lying in a bed just feet away from children with iron lungs and paralyses that would soon end some of their lives.

Today, although I live in a country and world besieged by conflict and Covid-19, I still feel blessed by this anniversary’s mixing of memory and medicine. Their combined prognosis is, perhaps surprisingly, one of hope and gratitude.

Mark Tochen, Camas, Washington

Journal entry, February 13, 2022

Thank you for asking for favorite pieces of music or art — what a wonderful request! Right away I settled on music because we respond so quickly to music. Art takes more time — the art studying technique called slow looking even expects that you take the time to really get to know an artwork. It’s remarkable, but not like being transported to pleasure in five seconds by a bar of music!

I chose from the Baroque Henry Purcell’s seventeenth century trumpet voluntary. Played with organ and trumpet, this piece ignited my sleepy self on a Sunday morning many years ago. The lilt of the trumpet conversing with the majesty of the organ greets the day with a call to joy — surely a song of morning, of a new day and new beginnings, of waking and dancing around the living room with your child in your arms!

Leane Cornwell, Mill City, Oregon

Journal entry, February 13, 2022

Any mid-February sunny day in the Pacific Northwest requires the doing of outdoor chores. Steve and I went to Bi-Mart for a few supplies to do ours. Found quickly, we headed towards the check-out counter. My thought of ‘It’s Sunday; we’ll be in and out in no time’ was very wrong.

As we rounded an aisle it was brutally obvious there would be a long wait in line. Only one register was open. I felt pity for the young man manning it.

We located the end of the line and were relieved to see a friend in line in front of the young man in front of us. Conversation ensued. Fishing was the subject and before I knew it, all three men were swapping fish tales.

Our words and laughter snatched up the young woman behind us. She was buying archery supplies and a target. Her children wanting to practice before competing at the camp bow range during their summer vacation. As we visited and the line forwarded, we passed the candy shelves. I couldn’t not pick up that Hershey dark chocolate bar.

Time passed quickly and our friend checked out.

Now it was the young man’s turn. He was returning an item for $31.99. Nolan, (we knew his name by now) the cashier, asked if he had a penny, he would give him $32. The young man didn’t. I said I did and offered it up.

Apparently, he had noticed me add the chocolate bar to the supplies I held. As he left, he gave the two dollars back to Nolan telling him it was for my bar.

Life is sweet.

Darci Wolcott, Indialantic, Florida

Journal entry, February 4, 2022

Today is Friday. We just finished playing Brahms’ Piano Trio in B major in my living room. We plan to play string quartets on Monday. I’ve been playing chamber music with dedicated amateurs for forty years. For many years, I was the pianist. I took up the cello in my fifties, and even now, after nearly 30 years, I still have to practice a lot to keep up with these dear friends who have been playing since childhood.

It’s worth it: our twice weekly sessions have kept us sane — at least, saner — throughout the pandemic. We open the windows, run the A/C and air purifier. We’ve masked, and vaxxed. Our “bubble” made it through until last month, when one of us had a brief bout with Omicron. The music is a respite from sadness and fear. We are totally engrossed as we try to translate black lines and dots on a white page to the language of beautiful sounds, let alone synchronizing the rhythms and dynamics of the masterpieces forwarded to us by the great classical composers.

We are not like the skilled professionals who share their talents with others. But today, we did our best for Brahms. It’s very complicated music, full of emotion. We are exhausted and thrilled, and the sublime music will continue in our heads for days.

Stephen Kingsnorth, Wrexham, Wales

Journal entry, February 1, 2022

In response to Passager’s call for members of the community to share what art, music or literature inspires them these days, I would have to say the composer Edward Elgar. Pandemic or not, he always works for me.

Because he wears the looks of an Edwardian English gentleman and reminds me of my great-grandfather.

Because he takes me to the Malvern Hills in Worcestershire fifty years ago, and I am drawing strings on the Christmas-gift kite on Boxing Day, battling the wind as I overlook three English counties — not in a vast panorama of global note, but in an ‘area of outstanding natural beauty’, the comforting understatement of a green and pleasant land. Because I can hear the swells and crescendos of ‘Nimrod’ from ‘Enigma Variations’ played at my funeral, as encapsulating the sheer joy of freedom.

*Elgar was best known for his Pomp and Circumstance marches.

Lucy Iscaro, White Plains, New York

Journal entry, December 26, 2022

Usually when we would celebrate our interfaith, blended family, celebration the hardest part would be getting the latkes just right and making sure all the gifts were wrapped. This year has a new addition to the preparations. The Covid rapid tests. A friend of mine celebrated with her children last week and half of them came down with the Omicron variant. We can’t risk the children’s health. Nor can we risk our own. We are, no matter how well we feel, in our vulnerable seventies.

It was uncomfortable, or to quote one of the grandkids, gross. But we all did it and thank goodness we were all safe to be together. And it was exciting to be setting the Brunch table with the extra leaf in it for the first time in two years.

I offered to make eggs to order. Then our oldest grandson, just a week out of his own Covid quarantine said he would be the egg chef. I didn’t even know he could make food! He proceeded to execute perfect egg dishes for himself and several of his cousins. I was touched and proud. I saw this 25-year-old man at my stove but at the same time I saw him as the tiny toddler who rattled my pots and chanted, “Cook, cook.”

Antoinette Kennedy, Hillsboro, Oregon

Journal entry, February 7, 2022

My mother’s spirit leaps from her drawing of the hunting dogs. Born in 1909, she was a teenager or maybe young adult when she created this, framing the piece in beige matting. The pen-and-ink has hung in our family homes for ninety years. It is mine now. Friends ask, “Were these your dogs?” I laugh. Growing up we had dogs, but they were part mutt, part spaniel. They romped in the neighborhood, splattered mud on the linoleum, and gave us litters with unknown blood lines. No, this painting is all of my mother, the artist of noble head and fine bones. My mother, doubled in elegance, who, even now, lifts her head, stares toward far horizons, and bounds toward beauty.

Teresa Elguézabal, Baltimore, Maryland

Journal entry, February 2, 2022

In the parking lot, a woman sits on the curb near the library door, looking forlorn. It dawns on me that, under the pandemic schedule, I’ve arrived early. Through my passenger window, I tell the woman, “The library doesn’t open until noon.”

“What?” she asks.

We have to repeat ourselves until she asks, “¿Ha-bla es-pa-ñol?”

Something about my speech, my hair and eye color — I assume — led her to guess right. “Sí, también ingles,” I say (English also).

“Está muy linda,” (pretty) she says, and I smile: “Gracias.”

From her cautious pronunciation, I figure she’s not a native Spanish speaker. Yet she knows that pronouns are integrated in verbs. I compliment her Spanish. She gives me a thumbs-up, and I return the gesture from inside my car. If not for the modified library hours, we wouldn’t have had this time to become buddies. We protect ourselves from infection with separation, yet Corona virus brought us together.

“My name is Rhonda,” she says.

The security guard tells her the library will open soon. “Move away from the door.”

“I’m talking to a nice lady in Spanish,” she says, but he insists, “Move along.”

I don’t know how long Rhonda sat on that curb, but she appeared content leaving. She and I had, separately, escaped the quarantine of home and ended up chatting in Spanish. By daring to speak each language and meet others wherever they sit, we can mend what rips us apart.

Romana Capek-Habekovic, Grand Rapids, Michigan

Journal entry, January 27, 2022

The winter of 2021 was almost over when I decided to go for an early walk. The last snow melted exposing rotting leaves laid next to the asphalted path. The temperature was in low digits but above freezing. I put on my fleece-lined windbreaker, thick tights, earmuffs, and woolen gloves. Halfway through my route, I noticed that my usual maskless elderly strollers, my contemporaries, were missing. I attributed that to their waiting for the afternoon sun that the forecast had predicted. Instead of my usual focus on the rapid pace I try to keep, I slowed and observed the surroundings. Suddenly, I noticed a slight commotion on the thin layer of leaves. Out of it sprang a small bright yellow butterfly that proceeded to fly in front of me. I ran to follow it. I felt that wherever the butterfly took me there would be a new beginning. He was a messenger of hope, that phoenix is still possible. My chase ended when the butterfly soared above my head and disappeared into the woods. I resumed my walk at a slower pace and smiled as if trying to make the whole world smile with me.

Miriam Karmel, Minneapolis, Minnesota

Journal entry, January 30, 2022

We’re hunkered down. Again. Temperature hovers in negative territory. Omicron tears through the country. Restaurants, airlines, theaters, subways are cutting back because too many workers are sick.

This morning, at the start of yoga class (Zoom! Zoom!), Guru Nancy remarked on people saying they can’t wait to get back to the way things were. “I think what they mean is, they want to be free.” She said that even before the pandemic, Buddhists spoke of finding freedom in each moment. “You can have freedom now.”

Later, I told B, “We have to step up our game. At dinner, we will dress up. Not top hats and tails; high heels and chiffon. But we have to do better.” B has taken to wearing saggy pants around the house, and a trio of untucked shirts wool plaid, tee, pinstripe. The layered-look run amok.

I’m thinking back to a summer in Italy when all the writers in our workshop dressed up for dinner, on a terrace overlooking the valley. We wore treasures gleaned from local markets — silk shawls, embroidered blouses, amber beads. We wore lipstick.

Now I remember Susie saying, “Put on some lipstick, you’ll feel better.” Tonight, I’ll take my sister’s advice and color my lips a shade aptly called, Brave Red. I’ll wear a necklace and pretty shawl. I don’t expect B to put on lipstick, but he will tuck in a fresh shirt, and shave. Together we’ll reclaim a bit of the way things were.

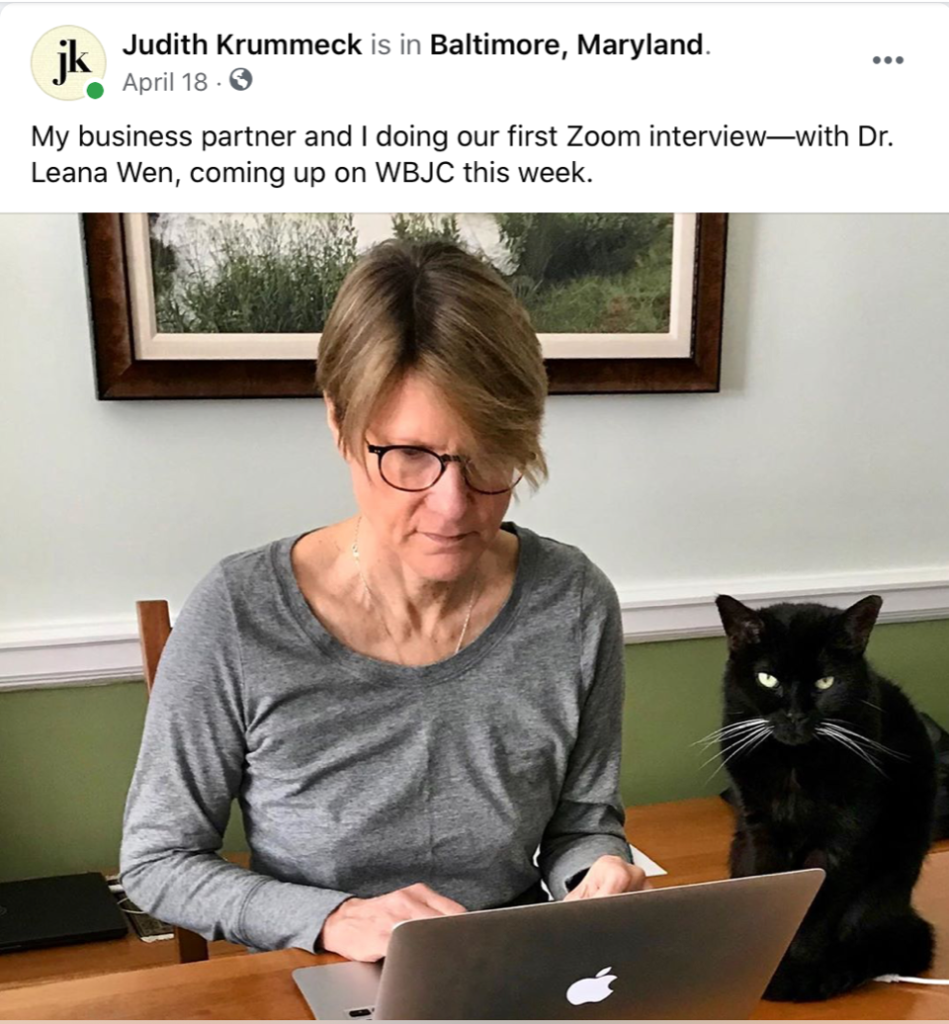

Judith Krummeck, Maryland, USA/South Africa/Zimbabwe

Journal entry, January 26, 2022

As I write this, Sasha is chowing down on her breakfast from a bowl that has a matching black kitty at the bottom of it. Thelma has spent another night firmly locked against my hip in bed. They missed me, and I them. Against all odds, including four touch-and-go COVID-19 tests, I’m just back from that other place I call home.

Was it reckless to go? Yes. Was it worth it? Yes, and yes. The omicron variant, identified by my astute scientific compatriots in South Africa, has peaked there and, being summer, we could all gather outside. First touchdown in Cape Town, my soul city, catching up with Erica and Peter; a quick run-up to remote Koringberg for afternoon tea with Hillary and Trevor; then to Hermanus to overnight with them in a family home overlooking the Indian Ocean. On Friday, a flight to Johannesburg, and a drive east to Millstream in Mpumalanga, with the welcome committee being a group of zebras. Where we were married. Twenty-five years ago. On January 18th. How could we not hold fast onto the dream of celebrating our silver wedding anniversary there, COVID-19 notwithstanding? And to be there with Jan and Julia, who celebrated with us all those years ago. The added bonus — a flight to Victoria Falls for me to see this indescribable Wonder of the World for the first time in my life.

So now, jetlagged and replete with memories, I remember the smells, the warmth, the unique beauty, the honking calls of hadedas, the irreplaceable friends. I think of having been home, from the place I now call home.

Marjorie Stuckle, New York, New York

Journal entry, January 18, 2022

I am sitting in my apartment, watching your funeral on my iPad. I am writing to you in this journal entry but you cannot hear me. I am thinking that the pandemic has intruded again, and this time it is robbing your friends of the intimacy, the comfort, of friends in mourning. We need each other. We would have gathered at a meaningful service, to say goodbye to you, finding a place to share our memories and drink a vodka toast to you. We had plenty of memories after all. I recall all those years, working together. So, while I could hate this distance from you and our friends today, I am grateful for this screen, for this funeral by iPad.

Because I feel the need to be quiet, to think and to remember your fun-loving, energetic, singing beautifully, life. And of course I will toast you, old friend, in my apartment tonight. You were a character!

Barbara Buettner, Fanwood, New Jersey

Journal entry, January 16, 2022

Today, a miracle of sorts: I hear my aunt’s voice. At 10:30 the temperature has reached 14 degrees and, possibly because of the cold, I decide to call my aunt Georgette who lives in Montreal. It must be even colder there. Sunday mornings was when I called her for over 18 years, since my mother died. But for about a year, her aides have forbidden her the phone, knowing that with her lapsed memory, she often calls her children up to 20 times a day.

On the other end of the line, her voice appears. I conjure up her face with ease. She is 102 years old now and we have had a long relationship. I remind her carefully who I am, whom I married, and the names of my child and grandchildren, and of course, my mother’s name. She doesn’t remember clearly but she works at it nonetheless. She wonders why I’m not there and I remind her that I live in New Jersey and won’t be able to visit until virus restrictions lift at the Canadian border. I remind her that I sent a picture a month ago and she is blank, saying she never received it. The aide shouts out that she did and says she’ll show her later.

It’s hard for her until we turn to lighthearted things — the weather, her latest activities, her recent birthday party. She doesn’t feel 102, she tells me. I ask her how old she feels. 24? I suggest. “Now don’t exaggerate,” she says, laughing. “Maybe 40” she insists. We joke a little in the here and now, she throwing in French words that come from deep in her unremembered world.

No matter that she doesn’t conjure up my face or who I am. I can see hers as if she is in front of me. I can conjure up the years of love in her presence, the feeling of belonging in her life the minute I crossed the threshold to her house and sat at her kitchen table with tea served in fancy porcelain cups. I feel her arms around me as I leave to return to “The States,” see the tears in her eyes and hear her injunction for us to hurry back. See her joking with my husband, whom she also loved but no longer remembers. I think of the summers she so generously took care of my younger sisters in the shadow of my young father’s death. I don’t mention their names, though she loved them. This conversation is enough now. I don’t want to cause some pain deep inside a brain that has begun to change.

So she doesn’t remember me, and maybe she doesn’t even remember my mother, her favorite sibling, whom she adored. I’m afraid to ask. I keep the conversation light and cool for this woman whose fading memory is something she’s entitled to at 102. I am so grateful to have unexpectedly heard her voice today. Even if I never talk to her again, today was like a Sunday miracle.

Fred Karlip, Baltimore, Maryland

Journal entry, January 24, 2022

Despite having gotten the vaccines, a medical condition has left me highly susceptible to COVID. Consequently, I’ve been stuck at home for a long time. And the question is always . . . what to do?

As I stare out the living room window it occurs to me that maybe I should do something nice like feed the crows. It’s so cold and nasty outside, I think the crows could use a little love in the form of food.

According to the Internet, since they’re scavengers, they eat almost everything. I did get some suggestions on some of their favorite foods, and I happen to have some real crow goodies, including raw peanuts, bits of cut up apple, broken pieces of matzoh, dog kibble, cut up chicken hotdogs, and Rice Chex.

Crows can produce intelligence equal to that of a seven-year-old. They can problem solve using multiple steps and tools (see examples on YouTube!). They can remember thousands of places where they have stored and hidden food.

I also learned that because they’re cautious, you need to conform to their expectations if you want them to trust you. They recognize faces and will categorize you as neutral, a friend who regularly feeds them, or an enemy who has threatened them. If they learn to trust you, not only might they eat your food but they may leave you gifts: some type of shiny object they found or maybe even a dead mouse. However, if you have offended them, you could very well be dive bombed.

Learning about, observing, and interacting with them has become my new hobby.

Rosanne Singer, Baltimore, Maryland

Journal entry, January 16, 2022

On December 27th, I got one of those reminders that life can change in an instant. I slipped on a rain-slicked mat outside an Airbnb, fell to the ground, wrenched my right ankle and frightened the upstairs tenants and my family with my hair-raising screams. The six steps up to street level were the last steps I’d climb for a while. An emergency room visit and x-rays showed a bad sprain. I left the hospital several hours later with crutches, an air-cast and my husband and daughter on either arm.

A few days later back home in Baltimore, I started coughing and noticed that my husband’s morning coffee smelled foul. On January 3rd, I tested positive for COVID (despite being vaxed and boosted) and have spent two weeks cycling through an array of symptoms from congestion to chest tightness to coughing to low fever. I’ve left our apartment just once, to get fitted for a CAM boot for my ankle. My husband and I have lived like masked strangers, never touching, keeping distance.

I’ve also cycled through an array of emotions in these past three weeks. I’ve cried out in pain and self-pity; I’ve been short-tempered with my husband and beyond grateful; I’ve made jokes and been humorless; I’ve felt connected to friends and family through phone, text and email, and at the same time felt mightily bored, alone and lonely.

The world is going through some tough gyrations, but I can’t wait to rejoin it. I’m looking out the apartment windows a lot and longing to walk our dog, return to the Saturday farmers market and taste the snow I can see coating the tree branches.

Jane Seskin, New York City, New York

Journal entry, January 16, 2022

Frigid winter day. No plans. Went down to the lobby of my apartment house, mask in place and sat on the tweed sofa off to the side. Watched my neighbors enter and leave while I happily stayed put. Saw some nice puffer coats.

People paused in their day to stop and talk. There was a spirit of catch-up. I witnessed conversations and learned of some who’d been broken by the losses of the year. Some of these people I’d grown old with, watched their children grow up and out. With a few I laughed, how good that felt and with others sighed over changes in the neighborhood. The lobby time was connection. It was community.

Gathering together was an elevator ride away. Easy. I need to remember to be among the voices, because that’s what contributes to my humanity and gratitude.

Lev Raphael, Okemos, Michigan

Journal entry, January 3, 2022

I wake up every morning feeling like David Byrne in a classic Talking Heads song as he laments, “How did I get here?” Because as the song says, this is not my beautiful life. That disappeared two years when I stopped traveling in the U.S. and abroad, stopped seeing friends for lunch or dinner, stopped feeling safe in the world. Yes, I wear a mask when needed and have had my vaccinations and booster shot, but at 67, I feel endangered and besieged.

In the beginning I almost had panic attacks leaving the house to go on a simple shopping run. I’ve calmed down over these long months, but any news flash about rising infections or the new variant coming across my screen pushes a button I wish wasn’t there.

My professional life has been damaged: as a writer I haven’t been able to do the workshops I was scheduled to do because they were cancelled. When my 27th book came out, the mystery Department of Death, public readings were off-limits.

I’ve learned how to enjoy near-solitude with my spouse of many years. And caring for two West Highland White Terriers has been an anchor because they need to be walked, fed, groomed, played with and loved as if nothing has changed.

Yet two years have been stolen from me and all I can do is write about the loss.

Dina Sokal, Baltimore, Maryland

Journal entry, January 10, 2022

Despite Covid 19 and fears of flying during the pandemic, we flew from Baltimore to Los Angeles to see our first grandchild, Elisheva. She was born on April 8th, 2020 after our family Passover seder conducted on Zoom. We didn’t see her until two and a half months later. We fell in love with her on the spot. She has wide blue-gray eyes that stare at you with a focused intensity, a dedication to learning all about the world. She raises one eyebrow in a quizzical look. She widens her mouth to smile and then the corners of it will go down in a cry. Her parents think she’s embarrassed. She looks at you with a feeling of love shouting at you and flowing through your heart. She cranks her arms and legs up and down in bent poses doing her own dance, a dance of being alive and alert. Her smiles lead to crinkling of her eyes and a way upturned mouth, bubbling with fun and amusement. She is now almost two — an advanced two-year-old beauty — a big personality. I fall into the trap of gender stereotypes and call her a sweet little girl, a sweet pea, our granddaughter, our gift!!

Mark Tochen, Camas, Washington

Journal entry, December 29, 2021

Passager’s Pandemic Diaries are a brilliant concept beautifully carried out — I love these journal entries! But there’s a ginormous elephant in the Pandemic room, and I can’t tiptoe around it any longer — the antivaxxers.

They include neighbors, friends, and family I love, but I don’t want to love them to death. As an old pediatrician, I’ve seen a few things — a roomful of young children lying on cots in a conference room become an improvised hospital ward, 40 children dying of measles encephalitis, surrounded by grieving, sobbing family members. And yet a year later an improved measles vaccine was saving lives leading eventually to measles’ eradication —

I remember seeing an old farmer spasming all over his hospital bed in a Virginia hospital, dying of tetanus, “never had a shot in my life,” his proud boast ringing hollow through the room —

And a British medical report detailed the sequelae of the British decision to take the “P,” pertussis, out of children’s DPT shots, and 5000 children unnecessarily died in the UK that year of whooping cough —

800,000 Americans dying of a wild animal virus from China despite amazingly quick vaccine development, most deaths occurring in the unvaccinated, reservoirs of potential disease mostly missing the vaccinated —

The word “science” comes from the Latin word scio, meaning “I know.” There’s no conspiracy against the unvaccinated, only researchers finding a way to protect us all, and in the arms of the willing we find safety.

Vaccines work!

Sandra Rivers-Gil, Toledo, Ohio

Journal entry, December 22, 2021

I don’t rush to hear the world news tonight because news has a way of writing itself perpetually into our culture . . . I see masked people disconnected from smiles, handshakes washed secretly with sterilizing gel, while national uprisings leave us shaking our heads. We are overkilled with numbness. I have been boxed in on Zoom and asked to stand on floor stickers six feet apart. But who follows directions anymore? To close the perceived gap, I found that extending grace, a simple hello or How are you? to a stranger standing in front or behind me in a Krogers or Walmart line makes a difference to someone that day. It seems that the distance placed between us has made us long distance runners trying to catch our breaths. Lately, when I’m driving, there is that one car flying past me, attempting to get somewhere fast, only to be stopped at a red light. Before the pandemic spread itself like a widespread blanket of disease and dislike, I believe we were being pushed toward the threshold of doing something collectively different.

Martha Patterson, Boston, Massachusetts

Journal entry, December 7, 2021

I went out to get the mail today and my neighbor Herc was getting into his car. I hadn’t spoken to him in two months. He was going grocery shopping. He’s a retired music teacher and enjoys gardening in the spring and summer. On the small plot of land in front of his house he grows daisies, lilies, and iris.

“How are you holding up?” he asked and shook my hand.

“Covid’s hardly affected me,” I said. “I never go out except to the bodega.”

“It’s the best thing that ever happened to our economy,” Herc said. “People won’t

be wasting their money going out so much. I’m a Socialist. I don’t believe in throwing money around.”

I turned away as Herc got ready to drive off. When I went back into my apartment after shaking hands with him, I washed my hands with lavender soap. It smells floral and English and ladylike. And in washing my hands I wanted to be careful — you don’t want to argue too much with good health.

Maureen Murphy Woodcock, Cathedral City, California

Journal entry, December 18, 2021

Today, almost everything I needed to remember dodged me as if I was a dogcatcher after a feral cat. The first escapee was the recipe I know by heart. It isn’t written down because I’ve been baking those same damn Christmas cookies for half a century. After taking a few calming breaths, I told myself it didn’t matter. People were probably sick of getting my Jeweled Fruit Cake bites. Soon as I dismissed the memory loss, voila, the recipe came back to me. But I’m still going to bake something different this year.

Then there were those multiple trips halfway down the hall when I lost “what” was it I was going after. Finally, I commanded myself to metaphorically put on my sister Colleen’s orange helmet filled with brain glue. Like magic, it worked. And like always, I laughed at myself. Who cared if it took another trip to reload the toilet paper in the guest bath?

Forty-five years ago, when Colleen was in her early 20’s, Colleen told me she was going to draw a picture of all the things that kept falling out of her head. She decided to design an orange helmet to drip brain glue into her head to plug the up the holes. As she headed for the honey in my larder to mix up her glue, I suggested she paint a picture instead.

Which she did. I now have her genius on my wall. Looking at it soothes and tickles me.

Mark Tochen, Camas, Washington

Journal entry, October 16, 2021

I am now a connoisseur of walks, our main activity during pandemic times. Our basic walk a two-miler with courteous neighbors crossing the street to let us seniors pass, many sidewalk chats — “Jim, garden’s beautiful”, “Christine, glad real estate gave you a break.”

Our neighbors are gardeners and storytellers. Brian the retired cop visited our spring garden with his granddaughters, taking home flower photos and a bucket of flowers for their mom. Brian later called out as we walked by, “Helen, Mark, wait up! I have fresh-baked baklava for you.” I said, “Brian, no one has ever come running to hand us baklava!” We walked away munching baklava warm from the oven.

We walked white Pacific Ocean sands at Seaside, kids hung their sandals on a driftwood snag. We walked a lakeside path with runners, families, bikers, and moms pushing strollers passing politely, almost apologetic — “on your left — sorry!” One guy broke the tranquility, pumping hard on a mountain bike in mid-path, shouting “hoy” at every curve. I shook my head in concert with another pair of seniors, who said, “he’s sure in a hurry.”

Walking along the Columbia River, we saw barges and sailboats mingling in mid-river and a stern-wheeler churning upstream. Another couple took our picture, framed between beachgrass swaying above our heads and abandoned pilings now claimed by osprey nests. Glorious walks — metaphors of delight, defiance, and defeating this pandemic!

Cathy Lipski, Port Crane, New York

Journal entry, November 28, 2021

Almost two years have passed since the pandemic began. Since I have more years behind me than in front of me, I have focused on finding happiness, and have found it in an unsuspecting place; my swing that hangs from my tree.

The pandemic winter was long and a snow covered swing can be a challenge. It can also bring happiness and humor.

In the spring, I sit on my swing and watch sunsets. There’s strange contentment in being alone. As seasons change, so does my tree. Caterpillars crawl on branches and insects scuttle about. When I swing, I pretend life is normal. As summer fades, familiar birds are replaced by unfamiliar visitors. The leaves on my tree change color, texture and shape. I am changing, too, just like the leaves.

One afternoon, I left my swing and tree. A friend and I hiked a trail with views of gorges, golden leaves, meandering rivers and waterfalls. We weren’t the only ones trying to escape, find peace or find clarity. There were smiles on maskless faces. Photographers stood motionless trying to stop time. The pandemic seems to have both stopped time and made time pass quickly.

We feel vulnerable, unlike the gorges, trees, rivers and waterfalls. They remain constant and steadfast. Perhaps we can be hopeful by following their example.

Maybe the next pandemic winter won’t be so long if I brush the snow from my swing.

Leiah Bowden, Rohnert Park, California

Journal entry, November 16, 2021

When the pandemic closed down our worlds, I started walking along a creek near my home. I walked from three to six miles every day.

In August of 2020, the heat rose, so I stopped walking every day and walked less when I did venture out. When fire season came soon after, the smoke in the air kept me inside.

When the weather cooled and the smoke cleared, I started walking again but pain in my left hip and in my lower back stopped me in my tracks. I began a round of visits to physical therapists, chiropractors and massage therapists. The treatments mostly worked, but my left hip is still stiff and walking isn’t comfortable.

Last week I had the great good fortune to visit Sedona, where those magnificent red rocks pulled me out onto trails every day. The last day we were there, we hiked Fay Canyon, a mostly gentle, red-dust trail. There’s a side trail up to a shallow cave (the Arch, it’s called) that required some serious rock-scrambling. I made it halfway up and then honored my legs’ jellied demand that I stop.

As my friends and I walked back to the parking lot, I was in the lead, striding. Striding! No pain! No stiffness! I now know that while it may take a half mile to limber up, what my body needs is the good stretch of walking.

Onward!

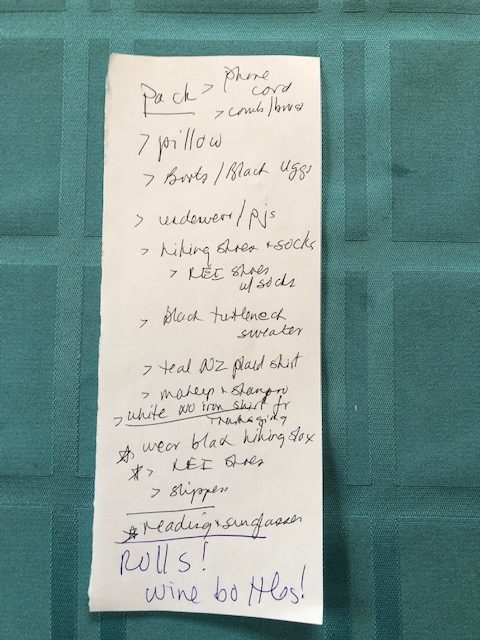

Debra N. Diener, Arlington, Virginia

Journal entry, November 21, 2021

This Sunday I’m busily building my “to take/don’t forget” list. I realize I’m feeling rusty doing so. I used to write out these lists on autopilot. But I haven’t done since 2019 — the last time we got together with family for Thanksgiving. But now that everyone’s vaccinated my family can be together.

In past years, I often felt stressed writing out these lists, fretting over what I might have forgotten or feeling rushed. So much to do to get ready and then facing that drive! Not today, not this year. Today I keep smiling and feeling happier with each item I’m adding. What a joy it is . . .

Beverly Boyd, San Luis Obispo County, California

Journal entry, November 6, 2021

For more than a year and a half I’ve grocery-shopped once a week at 6:30 am on Sundays when only a handful of people, other than the devoted employees, roam the aisles. I began this routine in May 2020 after encountering hostile, unmasked shoppers, aggressive in their efforts to come too near, daring me with hostile eyes to object, turning shopping into a nightmare.

A struggle at first, I eventually learned to enjoy the dark silence and empty roads, the morning mist, the lights already lit in the house of friends, the almost-empty parking lot. After friendly chats with the produce men, who arrive two hours earlier, I am ready to hunt and gather food for the week.

Leaving the store, I am welcomed by a glorious sunrise or the hint of one, depending on the season. Since my home faces west, I’ve become a connoisseur of sunsets. These shopping mornings, though, have allowed me to revel in morning skies, whether laced with clouds, dripping with fog, or radiating light from a peeping sun. Sometimes gulls hover on light posts. Other days crows circle, also looking for bits of food. I park far from the entrance to extend these moments of joy as I push my cart eastward across the lot.

Without the pandemic, these mornings would not have been a part of my life. And tomorrow is another Sunday.

Mark Tochen, Camas, Washington

Journal entry, November 4, 2021

I am the cook in our Pacific Northwest household, with a cooking partner 3000 miles away named Elsje, a Dutchwoman who lives with her spouse in upstate New York. We cook for our households, which for me began precipitously with the birth of a grandson, my wife saying, “You’re the cook now! I have to help with the baby.” I’ve become a decent cook and Elsje a creative cook whose dishes are visual and culinary poetry. We’ve kept each other afloat in these pandemic times. Her side job – attorney mediator/arbitrator and a four-term magistrate in her county; mine – 40 years as a pediatrician; our main occupation is as cooks and companions for our spouses.

We started with food photos – my previous food photography was the occasional family-around-the-Thanksgiving-Turkey picture, but Elsje LOVES food shots: “Here’s dinner: Norwegian salmon, steamed broccolini, and rice.” In self-defense I began to snap food shots with commentary. Thus began a dialogue of texting, photos and notes. We also traded information – “Wegman’s is the most amazing grocery store; we couldn’t live anywhere without a Wegman’s” or “Great oriental foods in the freezer section at Costco, soba noodles, vegan spring rolls, and potstickers.” We’ve learned from each other, and just completed a food journal, a two-volume set of kitchen wisdom, 60 pages with hundreds of photos, titled, as one might guess, “Cooking in Pandemic Times.”

Antoinette Kennedy, Hillsboro, Oregon

Journal entry, November 1, 2021

Michael,

I thought I had written my last letter to you in September. Sadness was wearing me down and anyway there were only a few notebook pages left. But here I am again. The University Hospital body donor letter came – asking for a photo for their video presentation. Remember when you said, “Maybe they can use this old carcass of mine”? I found the photo of you outside Amsterdam. You always did love all things Rembrandt. I sent them that one. Gold-orange leaves scurry outside my bedroom window. The sun juggles color, but the wind is cold. Did I tell you I wear your old cap? At night your plaid throw keeps me warm. Almost a year now. COVID at its height couldn’t touch you, but that other C sure did. At least, dearest brother, we did get to hunker down with PBS, and peanut butter and crackers. The other day I played your World’s Greatest Arias CD and listened to Nessun dorma and sat looking out at autumn, and cried, overwhelmed once more with missing you. I need to be done with mourning and would be if weren’t November again. Too much time. Never enough.

Miriam Karmel, Minneapolis, Minnesota

Journal entry, September 30, 2021